Roberto Burle Marx, Copacabana Promenade - Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (Source: BurleMarx&Cia Ltda)

Landscape architecture is an interdisciplinary profession that harmonizes art, science, and nature to design outdoor environments that are not only beautiful, but also functional, inclusive, and sustainable. It is the practice of shaping the land to meet human needs while respecting the processes of the natural world. From urban parks to rural riverbanks, from private gardens to expansive ecological networks, landscape architecture creates meaningful places that reflect the values and aspirations of a society. It considers the interplay of topography, vegetation, water, built structures, and social activity, orchestrating them into experiences that foster well-being, community, and environmental stewardship.

A Journey Through Time: The History of Landscape Architecture

The history of landscape architecture is as old as civilization itself. Ancient cultures such as those in Mesopotamia and Egypt developed gardens as sacred, enclosed places—symbols of paradise, representing harmony between humans and nature. In Persia, the Chahar Bagh design expressed order through quadrants divided by water channels, influencing garden design across cultures.

Greek and Roman societies made strides in the use of public space, introducing forums, agoras, and urban courtyards that formed the nucleus of civic life. The Romans, in particular, integrated architecture and landscape in their villas and cities, leaving a legacy of structured, formal environments.

During the medieval period, European landscapes became more utilitarian and spiritual, often enclosed and inward-facing. Monastic gardens served both contemplative and medicinal purposes, echoing a spiritual connection to the land.

The Renaissance and Baroque eras marked a return to classical ideals. Italian Renaissance gardens, such as those at Villa d’Este, featured terraces, fountains, and sculptures that celebrated human intellect and control over nature. French Baroque gardens, like Versailles, showcased grandeur and symmetry on a monumental scale, reflecting the central power of the monarchy.

Frederick Law Olmsted: Central Park, NY, USA (Source: shutterstock_worldatlas.com)

It was in the 19th century that landscape architecture emerged as a recognized profession. Frederick Law Olmsted, often called the father of landscape architecture, saw green space as a democratic right. His work on Central Park introduced the idea that urban parks could serve both as social equalizers and as essential lungs for growing cities. As cities expanded and the Industrial Revolution changed the landscape, landscape architects were called upon to shape parks, parkways, campuses, and suburbs.

The 20th century saw the rise of ecological thinking. Designers like Ian McHarg championed the integration of natural systems into planning. Postmodernism later brought a renewed interest in cultural narratives, aesthetics, and community-based design. Today, landscape architecture continues to evolve, facing new challenges such as climate change, environmental justice, and rapid urbanization, while embracing digital tools and interdisciplinary approaches.

Understanding the Elements of Landscape Architecture

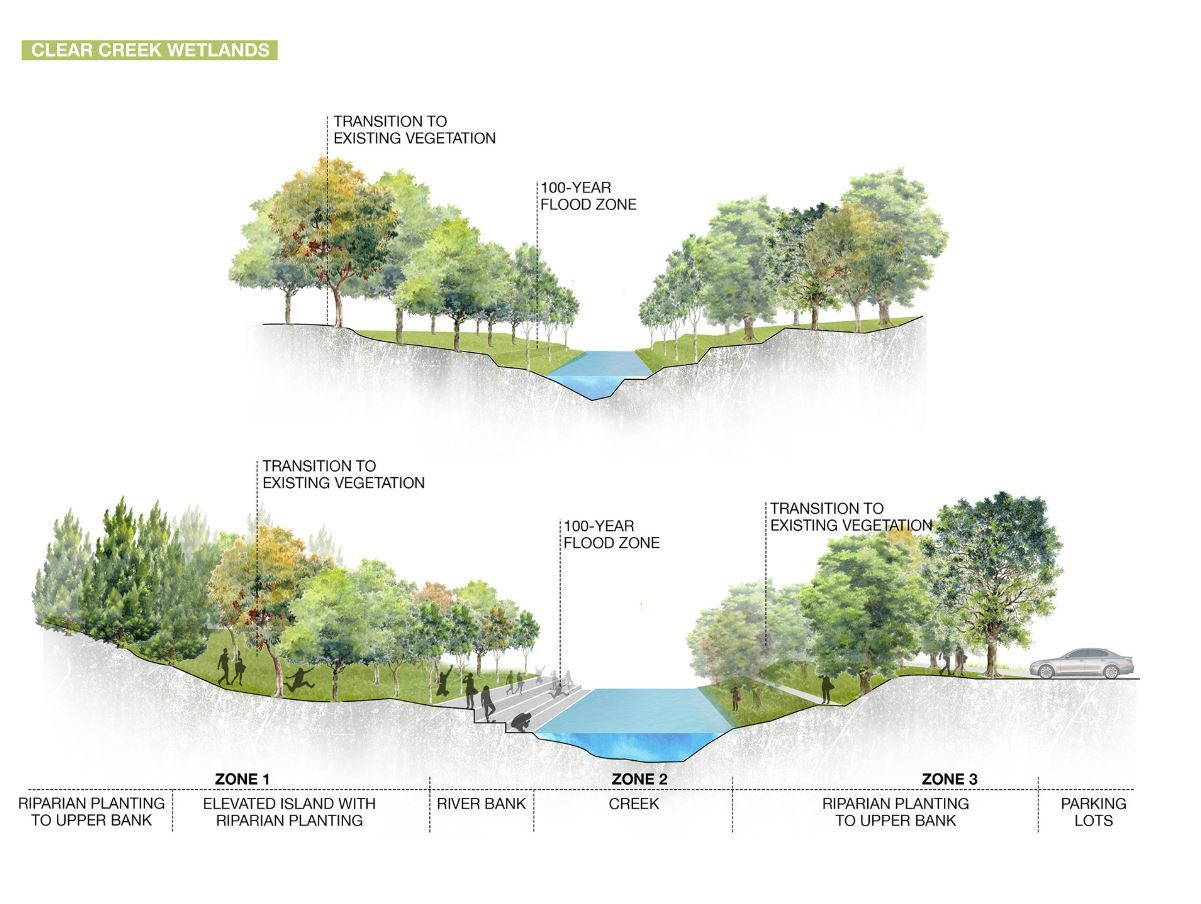

Section: Clear Creek Wetlands. (Source: landspace arch_benhance.net)

To fully understand landscape architecture, one must explore the elements that make up a designed space. These elements are not mere components—they are the building blocks of atmosphere, movement, and interaction.

Natural and Built Elements

The natural elements of landscape architecture include landforms (hills, valleys, slopes, and topographic features that define a site's character), water bodies (ponds, streams, fountains, and rain gardens that bring motion, sound, and cooling), and vegetation (trees, shrubs, groundcovers, and other plantings used for shade, colour, structure, and habitat). A rolling hill can create a sense of shelter or frame a view. A tree canopy can cool a plaza while offering a sense of grandeur. A pond or stream may bring biodiversity and tranquillity. These elements are carefully selected and placed not just for aesthetics, but for their ecological, sensory, and social value.

Built elements, on the other hand, such as benches, walls, pathways, pergolas, or bridges, add structure and usability. They shape how people move through and inhabit the space. The material choices—stone, wood, concrete, metal—contribute texture, temperature, and historical resonance. Good design weaves the natural and built seamlessly, so that each supports the other.

Abstract Design Elements Beyond the physical, abstract elements like line, form, colour, texture, and space play a significant role. Lines—whether the edge of a path or a row of trees—direct movement, organizes space and define boundaries. Forms can be bold or subtle, geometric or organic, creating rhythm and structure. Texture, from smooth paving to coarse bark, adds sensory depth and variation through plants and materials. Colour influences mood, while space—the arrangement of openness and enclosure—determines how people feel and interact within the landscape (user experience).

Principles of Landscape Architecture

Underlying every successful landscape is a set of guiding principles that bring order and meaning to a design. Unity ensures that all elements of the landscape work together in a coherent whole. Balance brings stability, whether through symmetry or dynamic contrast. Proportion ensures that spaces and objects relate comfortably to one another and to human scale. Rhythm is achieved through repetition and variation, helping guide the eye and the body through space. Emphasis is used to highlight focal points or key features, creating moments of pause and significance. Above all, landscape architecture seeks functionality and sustainability—spaces must not only look good, but serve human and ecological needs over time: spaces meet user needs and minimize environmental impact.

What Do Landscape Architects Do?

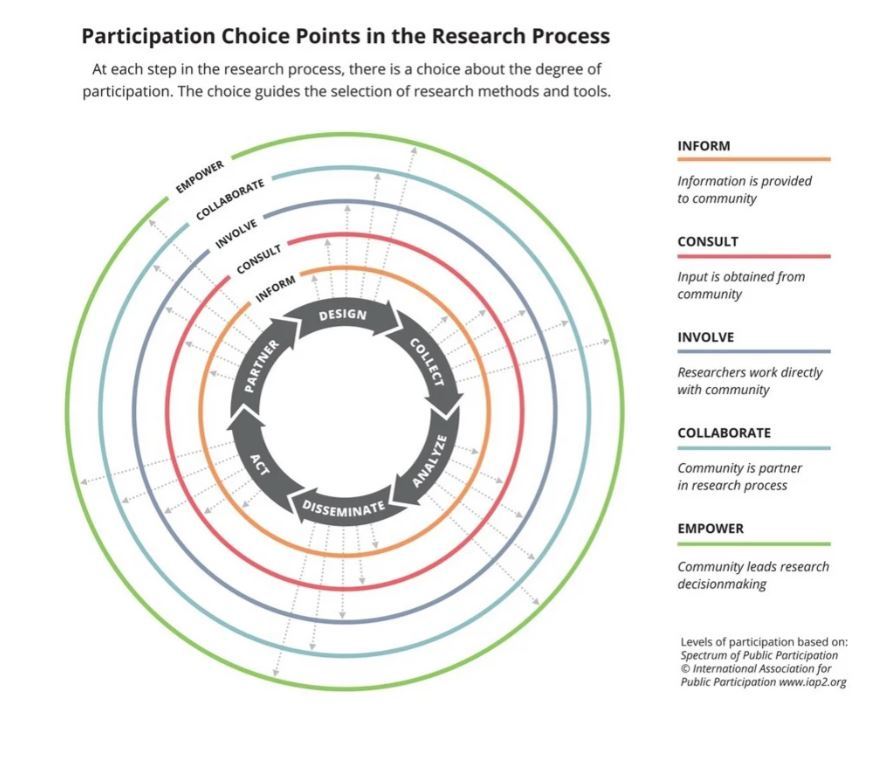

The role of a landscape architect is both analytical and imaginative. They begin by studying a site—its climate, soil, topography, hydrology, vegetation, and human patterns. They work closely with communities, listening to local voices and translating aspirations into form (participatory design)

Community engagement (Source: Vaughn & Jacquez_re-thinkingthefuture.com)

Landscape architects then move into design, developing concepts and masterplans that reflect the site’s potential. They select materials, propose planting palettes, and integrate ecological systems. Their work requires a firm grasp of engineering and environmental science (I.e. integrating stormwater management and ecological restoration), as well as a fluency in artistic composition. Collaboration is central—they often coordinate with architects, engineers, planners, ecologists, and artists.

In construction, landscape architects guide the implementation of their vision, ensuring that the design intent is preserved and that sustainability goals are met. Even after completion, they may monitor a site to evaluate its performance and adaptability.

The Versatile World of Landscape Architecture Projects

The range of projects that landscape architects undertake is vast and varied.

In urban settings, they design plazas, streetscapes, and public squares that encourage interaction and civic identity. These are the stages where city life unfolds—where people gather, celebrate, protest, and rest.

Exchange Square - City of London, UK (Source: dsdha_landezine.com)

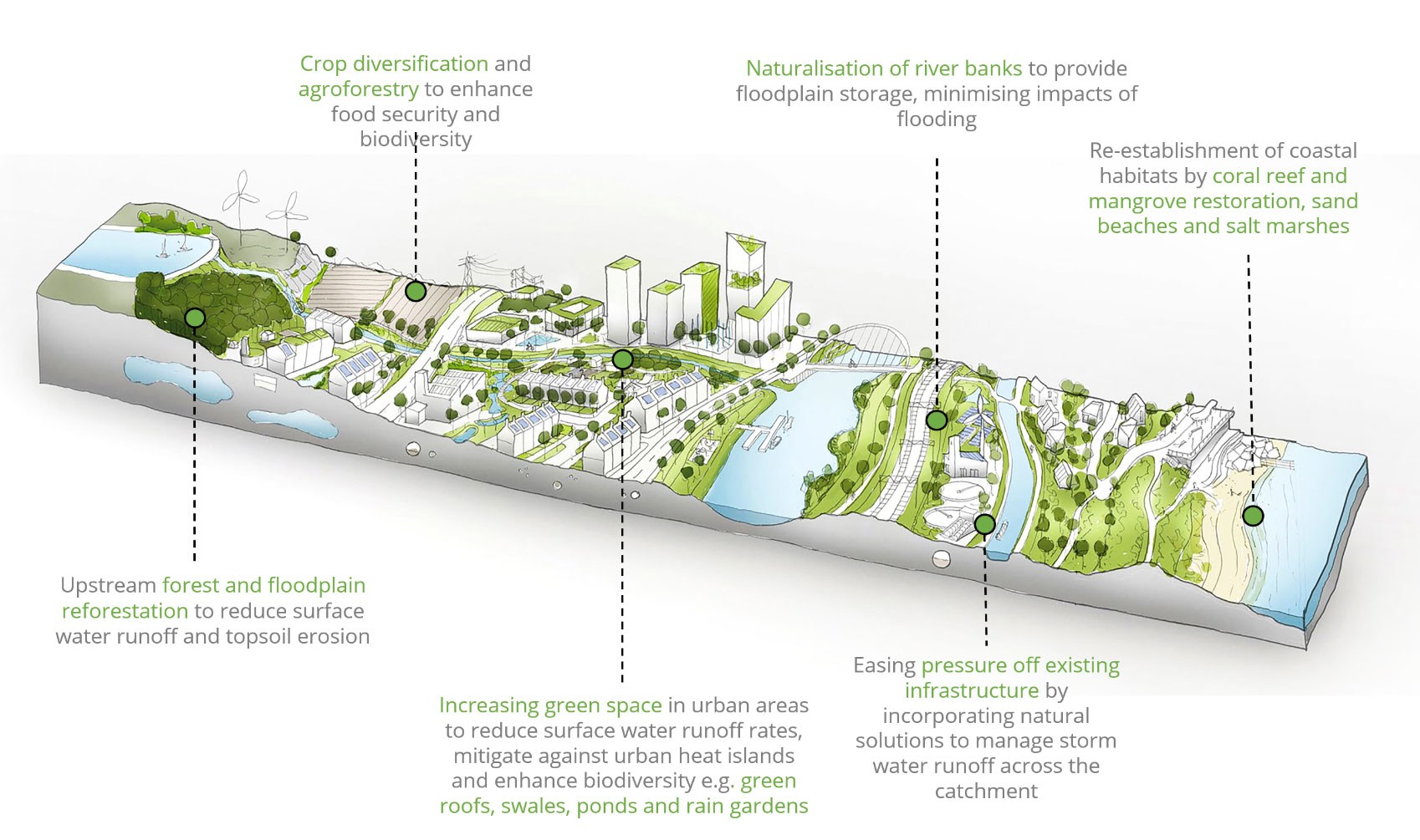

In ecological and environmental contexts, landscape architects are stewards of the land. They work on river restoration, reforestation, habitat creation, and climate-resilient infrastructure. These projects are not just about aesthetics, but about healing damaged ecosystems and supporting biodiversity (i.e. wetland restoration, rewilding, and watershed management to enhance biodiversity).

Johannisberg Wetland Park - Sweden (Source: Topia landskapsarkitekter_landezine.com)

Cultural and recreational landscapes, such as memorials, museums, college campuses, and public parks, are shaped to tell stories, support learning, and provide joy. These spaces hold memories and meanings, anchoring communities in place.

Residential projects offer intimate connections between people and nature. Whether a rooftop garden, a rural estate, or a suburban backyard, landscape architects create personalized environments that enrich daily life.

Preservation and restoration projects ensure that historical landscapes are not lost. Whether reviving an 18th-century garden or reimagining a forgotten industrial site, landscape architects honour the past while adapting it for present use.

Oakland Museum of California (Source: Hood Design Studio_Caitlin Atkinson)

Finally, infrastructure projects such as highways, rail corridors, and airports increasingly require landscape expertise to integrate green systems and human-scale design into what were once utilitarian zones.

Shanghai Super Tube - China (Source: Fish design)

Why is Landscape Architecture Important?

Landscape architecture is essential to the sustainability and liveability of our world. It has far-reaching impacts:

From an environmental standpoint, landscape architecture mitigates the effects of climate change by cooling cities, filtering pollutants, managing stormwater (bioswales, permeable paving, and wetland buffers), and conserving energy. It restores ecological balance through rewilding, native planting, and wetland protection.

For public health and well-being, green spaces are indispensable. They encourage physical activity, reduce stress, and foster social connections. Especially in urban areas, access to nature is linked to lower levels of anxiety and depression.

Economically, well-designed landscapes increase property values, attract investment, and enhance tourism. A vibrant public realm can transform neighbourhoods and spur local development.

Socially and culturally, landscape architecture gives communities a sense of place and belonging. It creates inclusive environments where diverse people can interact, celebrate, and express identity.

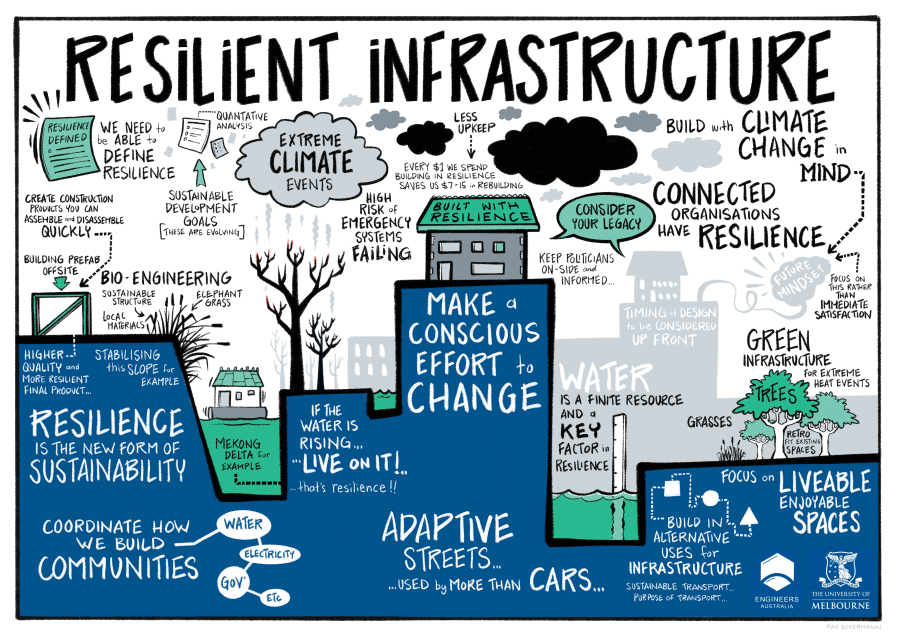

From a resilience perspective, landscapes are buffers against disaster. Green infrastructure can reduce the risks of flooding, landslides, and heatwaves, making cities more adaptive and self-reliant.

Resilient infrastructure (Source: eng.unimelb.edu.au)

Finally, in terms of urban planning, landscape architecture improves quality of life. It supports compact, walkable cities and helps align development with nature’s systems. As populations grow and cities densify, the role of landscape architects becomes ever more vital.

Challenges and Future Trends in Landscape Architecture

Despite its promise, landscape architecture faces complex challenges. Climate change threatens traditional models of design and demands bold, adaptive strategies. Water scarcity, soil degradation, and biodiversity loss require that landscape architects work not just as designers, but as environmental advocates.

Social inequality and displacement raise questions about access and justice in public space. Landscape architects must be attuned to the needs of marginalized communities and design spaces that are genuinely inclusive.

The future of the field is being shaped by emerging technologies and philosophies. Nature-based solutions, regenerative design, and circular economies are gaining ground. Digital tools like GIS, parametric design, and immersive visualization are expanding what is possible.

Most importantly, there is a growing recognition that landscape architecture is not a luxury, but a necessity. It is central to the future of cities, the health of our planet, and the well-being of future generations. As our world becomes more complex, the landscapes we design—and the stories they tell—will define how we live, relate, and thrive.

Nature-based Solutions – across different landscapes and hazards (Source: infrastructure-pathways.org)

Front pic: Japanese architect Junya Ishigami designed The Water Garden (Source: nikissimo.inc)

Featured Posts

Blog Topics

Urban environment & Public spaces

Stay updated with the latest articles and insights from The Landscape Lab. Here, you will find valuable information and engaging content.

Waterfront & Coastal Resilience

Stay updated with the latest articles and insights from The Landscape Lab. Here, you will find valuable information and engaging content.

Captivating Photography

Stay updated with the latest articles and insights from The Landscape Lab. Here, you will find valuable information and engaging content.

Why Read The Landscape Lab Blog?

The way we design and interact with landscapes is more important than ever. As cities expand, coastlines shift, and climate change reshapes our world, the choices we make about land, water, and urban spaces have lasting impacts. The Landscape Lab Blog is here to spark fresh conversations, challenge conventional thinking, and inspire new approaches to sustainable and resilient design.

If you’re a landscape architect, urban planner, environmentalist, or simply someone who cares about how our surroundings shape our lives, this blog offers insights that matter. We explore the intersections between nature and the built environment, diving into real-world examples of cities adapting to rising sea levels, innovative waterfront designs, and the revival of native ecosystems. We look at how landscapes can work with nature rather than against it, ensuring long-term sustainability and biodiversity.

By reading The Landscape Lab, you'll gain a deeper understanding of the evolving field of landscape design—from rewilding initiatives to regenerative urban planning. Whether it’s uncovering the forgotten history of resilient landscapes, analyzing groundbreaking projects, or discussing the future of green infrastructure, this blog provides a space for learning, inspiration, and meaningful dialogue.

Location:

The Landscape Lab

123 Greenway Drive

Garden City

NY 12345

United Kingdom

Contact Number:

Get in Touch:

contact@thelandscapelab.co.uk

© 2025 thelandscapelab.co.uk - Your go-to blog for landscaping insights