Introduction: Rethinking Waste in the Ocean Age

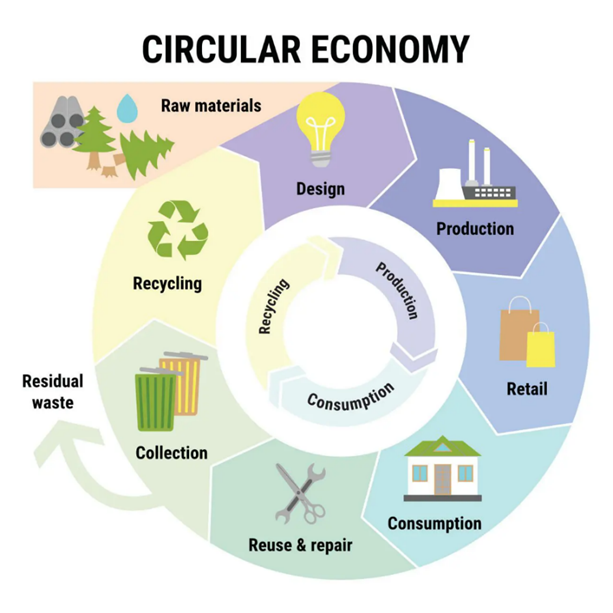

The blue economy—defined as the sustainable use of ocean resources for economic growth, improved livelihoods, and ocean ecosystem health—is gaining global traction as a framework for ocean-friendly development. But a major challenge remains: the linear, extractive model upon which most marine industries are based.

From discarded fishing nets and plastic debris to single-use marine packaging and unsustainable construction practices along coasts, waste and pollution threaten the ecological foundations of the blue economy. Enter the circular economy—a regenerative model that designs out waste, keeps materials in use, and restores natural systems.

The intersection of circular design and the blue economy is a critical frontier for innovation. Designers, planners, architects, and landscape architects are stepping into new roles—not just as form-makers, but as systems thinkers and material innovators. By collaborating with marine scientists, engineers, and policy makers, they can drive radical changes in how marine products are conceived, built, used, and reused.

(Source: iStock - our-blue-future.org)

1. Design for Reuse in Fishing Gear and Marine Construction

Current Situation

A fundamental pillar of the circular economy is the design for reuse—a strategy that reimagines products and infrastructure as systems with second and third lives, not single-use or disposable items. In the blue economy, two of the most problematic waste streams—fishing gear and marine construction materials—present immense opportunities for circular reinvention.

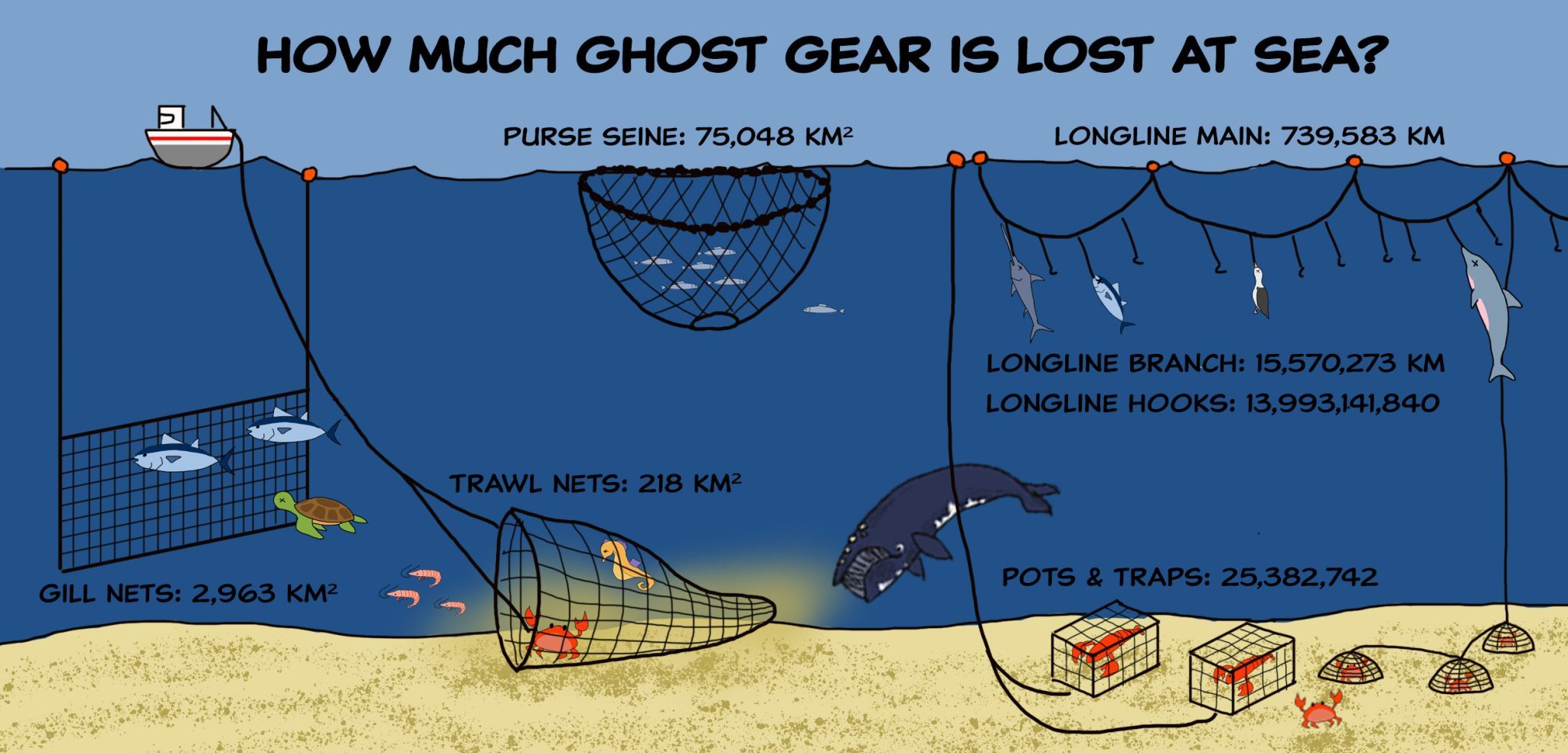

Fishing gear, including nets, lines, and traps, is often made from non-biodegradable plastics like nylon or polyethylene. Once damaged or lost, these materials become ghost gear, drifting in the ocean for decades, harming marine life and damaging habitats. Simultaneously, marine and coastal construction often uses materials that are hard to disassemble, recycle, or repair, leading to resource depletion and high carbon footprints. Despite rising awareness, most marine infrastructure is still designed for function over longevity, and gear is rarely built with end-of-life scenarios in mind.

Designers, architects, and engineers are now developing innovative systems where gear is modular and repairable, construction is demountable, and materials are selected based on life-cycle performance.

A study analyzed five fishing methods and estimated how much fishing gear is lost, abandoned, or discarded in the ocean. Illustration by Marina Wang with data from Richardson et al. (Source: hakaimagazine.com )

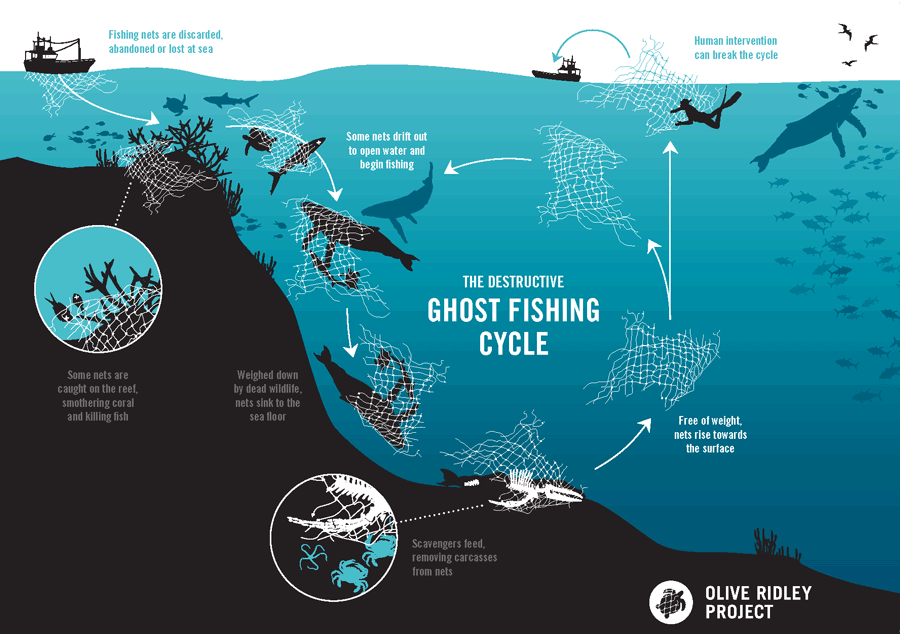

Ghost fishing refers to the destructive cycle of continued catching and killing of marine animals by abandoned, lost or discarded fishing gear. This so called ghost gear is no longer actively managed or attended to by a fishing operation or an individual fisher. Yet, it remains active, continuing to catch and kill animals, capturing anything in its path in an unselective manner. Entanglement in ghost gear often causes exhaustion, suffocation, starvation, amputations of limbs, and even death. This is a different issue than by-catch, which means the accidental capture of non-targeted species by actively managed fishing gear. (Source: oliveridleyproject.org)

Circular Design Approaches: What Can Design and Architecture Do?

Circular design in this context means creating gear and structures that can be repaired, recovered, repurposed, or biodegrade safely. It involves:

-

Modular gear systems that are easier to maintain and refurbish.

-

Take-back schemes led by manufacturers.

-

Biodegradable nets and lines made from natural fibers or bio-based polymers.

-

Circular marine construction kits with recyclable composites or demountable steel frameworks.

-

Integrate end-of-life scenarios into product and infrastructure design.

-

Design prefabricated, modular, or floating infrastructure that is adaptable and reusable.

-

Establish material passports that track the life and recyclability of construction elements.

Example: The Healthy Seas Initiative

The Healthy Seas Initiative is a flagship example of a circular collaboration involving divers, designers, engineers, and fashion brands. Launched in 2013, it recovers abandoned ghost nets from European seas and landfills and transforms them into high-performance textiles.

-

The collected nets are sent to Aquafil, where they are cleaned and regenerated into ECONYL®—a nylon yarn chemically identical to virgin nylon but infinitely recyclable.

-

ECONYL® is then used in fashion, furniture, carpet tiles, and even automotive interiors, proving that marine waste can enter high-value supply chains.

-

Brands like Adidas, Stella McCartney, Napapijri, and Interface have adopted ECONYL in their circular design strategies.

Importantly, designers have reimagined nylon not as a pollutant, but as a durable, circular resource. The success of Healthy Seas shows that a material’s origin doesn’t define its destiny—it’s how we design it into systems of value retention and renewal that matters.

“We are proving that the circular economy works—when science, industry, and design align with nature.” — Veronika Mikos, Director of Healthy Seas

“Design begins not at the drafting table, but with the material lifecycle. Circularity is not an afterthought—it’s the foundation.”

— Elisa Palazzi, Circular Product Designer, Healthy Seas

(Source: Rachel Kim_healthyseas.org)

Example: Circular Floating Infrastructure - Waterstudio.NL

Waterstudio.NL, founded by Dutch architect Koen Olthuis, is a world leader in climate-resilient floating architecture. With sea levels rising and usable coastal land shrinking, Waterstudio has pioneered modular, movable, and recyclable floating buildings for homes, schools, and even entire neighbourhoods.

-

These structures use modular pontoon systems and recyclable materials such as aluminium and concrete composites that can be disassembled and reused.

-

Floating systems can be reconfigured as needs change—from residential to hospitality or emergency shelters—making them ideal for cities with variable population density or risk exposure.

-

Their projects in Amsterdam, Maldives, and Miami demonstrate a model of construction that adapts with the climate and reduces long-term environmental impact.

“The future of cities is dynamic. Floating architecture allows us to design cities that flex and float instead of break.” — Koen Olthuis

(Source: waterstudio.nl)

2. Recycling Marine Plastics into Durable Products

Current Situation

Marine plastics—especially single-use items—account for an overwhelming share of ocean pollution. Over 11 million metric tons of plastic waste enter the ocean every year, and projections suggest this could triple by 2040 if current trends continue (source: Pew Charitable Trusts, 2020). Yet, once collected, most plastics face a lack of valuable end-markets. While cleanup initiatives have increased, they often lack end-markets for the collected waste. Without circular systems in place, the materials are either downcycled into low-value products—or worse, re-enter the environment.

Circular design aims to elevate ocean plastic from a symbol of pollution to a resource of possibility by using it in urban infrastructure, architecture, and industrial design.

Recycled marine plastics are being transformed into durable, high-performance products through innovative processing, design ingenuity, and storytelling that adds cultural and aesthetic value to waste.

Circular Design Approaches: What Can Design and Architecture Do?

Landscape architects, industrial designers, and architects are stepping in to create demand for recycled marine plastics by:

-

Designing public furniture, pavements, and urban fixtures made from ocean plastics.

-

Collaborating with artists and material scientists to transform marine debris into construction-grade panels or tiles.

-

Using circular procurement policies to encourage governments and developers to specify these materials.

-

Create demand for ocean plastic-derived materials by specifying them in public infrastructure and urban design.

-

Design products and systems that make use of local waste streams.

-

Create emotional narratives and tactile aesthetics that connect people to the origins of the material and the story of recovery.

Example: The PlasticRoad (Netherlands)

The PlasticRoad is a revolutionary infrastructure concept developed by KWS (a Dutch road construction firm) in collaboration with Wavin and TotalEnergies. It is the world’s first road made entirely from recycled plastic, including marine and post-consumer waste.

-

Each prefab modular segment includes a hollow core for water storage and drainage, reducing flood risk—critical for coastal and delta cities.

-

It’s lightweight, quick to install, and designed for easy disassembly and reinstallation—maximizing longevity and reuse.

-

The pilot projects in Zwolle and Giethoorn have proven its durability, with less maintenance required than traditional asphalt.

PlasticRoad embodies a circular, climate-adaptive design that gives marine plastics a new life within essential civic infrastructure.

A 100-foot-long cycle path was constructed in Giethoorn, the Netherlands. Image courtesy of PlasticRoad.

Example: Studio Swine’s Sea Chair

British-Japanese design duo Studio Swine created the Sea Chair—a stool made entirely from plastic collected from the ocean by fishermen.

- They designed a mobile micro-factory, mounted on a fishing boat, to melt and mould the plastic at sea.

- The project emphasizes the craftsmanship of waste transformation, where the product retains visible marks of its marine origin (e.g., shells, sand, colour swirls).

- Sea Chair challenges the perception of marine plastic as “garbage” and instead positions it as a design medium with narrative value.

“Our goal was to create something emotionally durable, not just materially durable.” — Alexander Groves, Studio Swine

“If waste becomes beautiful, it will never be thrown away again. That’s the power of design.”

— Azusa Murakami, Co-Founder, Studio Swine

Open Source Sea Chair by Studio Swine (Source: dezeen.com(

3. Biomaterials from Marine Organisms for Packaging or Construction

Current Situation

Biomaterials offer one of the most exciting frontiers in sustainable design—especially when derived from marine organisms or oceanic systems. These materials are naturally abundant, regenerative, and biodegradable, and many are by-products of marine industries (e.g., aquaculture, seafood processing).

From algae-based textiles to oyster-shell composites, designers are discovering ways to replace plastics, foams, and concrete with materials that sequester carbon, support marine ecosystems, and return safely to the earth.

Most marine and coastal construction still relies on high-carbon, non-renewable materials—concrete, steel, and petrochemical-based plastics. In contrast, nature has already evolved durable, regenerative materials in marine settings—kelp, chitin, shell calcium, and fish skin—that can be used for packaging, coatings, insulation, and even bricks.

However, these materials are vastly underutilized due to lack of awareness, industrial scaling, or regulatory support.

Circular Design Approaches: What Can Design and Architecture Do?

Marine biomaterials can replace plastic, concrete, and synthetic fabrics in blue economy sectors—while being compostable or even regenerative. Designers are exploring:

-

Algae-based bioplastics for packaging and single-use items.

-

Mycelium-fish scale composites for insulation and façade materials.

-

Crustacean shell biopolymers (chitosan) for water-resistant packaging.

-

Seashell-derived calcium carbonate in architectural cladding or bio-concrete.

-

Collaborate with biologists and material scientists to develop and prototype bio-based materials.

- Normalize bio-based aesthetics and textures in mainstream architecture and interior design.

- Advocate for life-cycle design, where materials are either regenerative or harmless in decomposition.

Example: Algiknit and Kelp-Based Textiles

Algiknit is a U.S.-based biomaterial startup that transforms kelp (a fast-growing macroalgae) into durable, stretchable fibers for use in fashion, furnishings, and industrial applications.

- Kelp farming is highly sustainable: it requires no fertilizers, no freshwater, and absorbs CO₂ as it grows.

- The resulting yarns are dyed using low-impact natural pigments and can biodegrade after use.

- Designers are using Algiknit in marine-adaptive fashion (like swimwear), interiors, and even coastal event structures.

Algiknit demonstrates how biomaterials can transform supply chains, reduce marine pollution, and create new economies rooted in ocean farming.

Issues such as tensile strength have been at the forefront of AlgiKnit's investigations. The Bioyarn created by them possesses sufficient strength and stretch to be hand or machine-knit in existing textile manufacturing infrastructure. (Source: materialdriven.com)

Example: Shell Homage by Newtab-22

Newtab-22, a Korean material design studio, developed “Sea Stone”—a terrazzo-like material made from discarded seashells from the seafood industry.

- Shells are ground and mixed with natural, non-toxic binders to form tiles, furniture, and building materials.

- The material mimics the look and feel of marble or concrete, but with vastly lower environmental impact.

- Sea Stone turns what would otherwise be acidifying landfill waste into a poetic material that connects architecture to the marine world.

“Every shell has a history—from the ocean floor to your home. Our work is about making those stories visible.” — Hyunhee Hwang, Co-Founder, Newtab-22

“Biomaterials are not just sustainable alternatives—they are aesthetic innovations rooted in marine ecologies.”

— Yasmine Abbas, Architect and Circular Materials Researcher

Sea Stone and the Art of Turning Seashells into Sustainable Construction Materials - (Source: architecturelab.net)

Conclusion: Designing Circular Seas

The ocean has long been seen as the final sink for waste. But in the age of climate change, marine biodiversity loss, and material scarcity, we must instead see it as a source of design inspiration, regenerative material cycles, and circular innovation. The transition to a circular blue economy is not merely about reducing harm—it’s about rethinking systems, materials, and aesthetics from the ground (or seafloor) up. Design, architecture, and landscape architecture offer tools not just for sustainability, but for regeneration, storytelling, and public engagement.

By working with scientists, engineers, and material innovators, designers can lead the shift from a linear, wasteful marine economy to one that mimics nature’s cycles—where nothing is wasted, everything has a second life, and the ocean is not a dumping ground, but a source of beauty, intelligence, and future possibility.

Through the lens of design, planning, and architecture, the circular blue economy becomes a vibrant opportunity: to reimagine products as systems, waste as raw material, and coastal cities as engines of ecological repair.

Whether it’s transforming ghost nets into luxury textiles, oyster shells into terrazzo tiles, or floating buildings into modular adaptive systems, the message is clear: the circular sea is not a dream—it’s a design problem. And we’re already solving it.

The future of the blue economy is circular. And the blueprint starts with design.

Featured Posts

Blog Topics

Urban environment & Public spaces

Stay updated with the latest articles and insights from The Landscape Lab. Here, you will find valuable information and engaging content.

Waterfront & Coastal Resilience

Stay updated with the latest articles and insights from The Landscape Lab. Here, you will find valuable information and engaging content.

Captivating Photography

Stay updated with the latest articles and insights from The Landscape Lab. Here, you will find valuable information and engaging content.

Why Read The Landscape Lab Blog?

The way we design and interact with landscapes is more important than ever. As cities expand, coastlines shift, and climate change reshapes our world, the choices we make about land, water, and urban spaces have lasting impacts. The Landscape Lab Blog is here to spark fresh conversations, challenge conventional thinking, and inspire new approaches to sustainable and resilient design.

If you’re a landscape architect, urban planner, environmentalist, or simply someone who cares about how our surroundings shape our lives, this blog offers insights that matter. We explore the intersections between nature and the built environment, diving into real-world examples of cities adapting to rising sea levels, innovative waterfront designs, and the revival of native ecosystems. We look at how landscapes can work with nature rather than against it, ensuring long-term sustainability and biodiversity.

By reading The Landscape Lab, you'll gain a deeper understanding of the evolving field of landscape design—from rewilding initiatives to regenerative urban planning. Whether it’s uncovering the forgotten history of resilient landscapes, analyzing groundbreaking projects, or discussing the future of green infrastructure, this blog provides a space for learning, inspiration, and meaningful dialogue.

Location:

The Landscape Lab

123 Greenway Drive

Garden City

NY 12345

United Kingdom

Contact Number:

Get in Touch:

contact@thelandscapelab.co.uk

© 2025 thelandscapelab.co.uk - Your go-to blog for landscaping insights