Understanding the Cultural, Aesthetic, and Experiential Dimensions of Marine Space

Marine spaces—oceans, coasts, estuaries, and seascapes—are too often viewed through a narrow, utilitarian lens. In traditional marine planning and governance, the ocean is treated primarily as a domain for resource extraction, economic development, and geopolitical management. This view reduces the ocean to zones on a map: places for shipping, fishing, tourism, or conservation.

However, oceans are far more than this.

They are deeply woven into the cultural identities, aesthetic perceptions, and emotional experiences of individuals and communities. They are sacred in many Indigenous traditions, embedded in art, song, and mythology, and central to spiritual, recreational, and historical relationships with place. Recognizing and designing for these dimensions is essential for creating truly inclusive, ethical, and resilient marine spaces.

1. Cultural Dimensions

The cultural dimension of marine space refers to how people attribute meaning, identity, memory, and belonging to oceanic environments. This includes:

-

Indigenous cosmologies that view the ocean not as a resource but as a relative or living being.

-

Traditional livelihoods such as small-scale fishing, canoe building, seaweed harvesting, or maritime rituals passed down through generations.

-

Maritime heritage, such as lighthouses, shipwrecks, port architecture, and navigation routes.

-

Place-based narratives and storytelling that give symbolic value to certain areas of the sea.

Incorporating cultural dimensions into marine spatial planning involves listening to local voices, engaging in story mapping, and protecting not just ecological resources but also intangible cultural heritage.

“To many coastal Indigenous peoples, the ocean is not a void or an empty space—it is a homeland with stories, ancestors, and rights.” — Dr. Rebecca Tsosie, Legal Scholar of Indigenous Rights and Environmental Law

2. Aesthetic Dimensions

The aesthetic dimension relates to how marine environments are perceived, appreciated, and represented visually and sensorially. While aesthetics are often considered subjective, they play a powerful role in how societies value and protect coastal and marine areas.

-

Scenic views, horizon lines, sunrises over the water, and coastal silhouettes shape the emotional attachment people have to marine places.

-

Artists and designers draw from the ocean’s dynamic forms—waves, tides, coral patterns—to inform architectural expression and public space.

-

Seascapes are used in national iconography, tourism branding, and cultural identity-building.

Aesthetic values should not be dismissed as “soft” or non-quantifiable. They influence policy (e.g. protected viewsheds), behaviour (e.g. coastal tourism), and land-sea interactions (e.g. real estate development).

In marine planning, designers can use tools like visual impact assessments, immersive modelling, and public aesthetic dialogues to ensure developments respect visual integrity and emotional resonance.

3. Experiential Dimensions

The experiential dimension encompasses how individuals physically and emotionally engage with marine environments—through swimming, diving, sailing, fishing, walking on beaches, or even watching the ocean from shore. This interaction is sensorial, embodied, and often therapeutic.

-

The ocean provides a sense of awe, freedom, fear, or transcendence—a profound psychological and emotional connection.

-

Marine spaces support mental health, recreation, and well-being—known as “blue health” benefits.

-

Access to the sea is a form of spatial justice, especially for marginalized communities who may be excluded from waterfront areas.

Designers and planners can amplify these experiential values by:

-

Improving coastal accessibility (ramps, trails, public docks).

-

Creating multisensory experiences (e.g., sound installations, touchable tidal pools).

-

Encouraging participatory stewardship—such as community reefs, floating gardens, or ocean festivals.

“People protect what they experience and love. The more people are immersed in ocean experiences, the stronger the social license for marine protection becomes.” — Prof. Sue Jackson, Human Geographer, Australian Rivers Institute

Integrating These Dimensions into Marine Planning and Design

Bringing these dimensions into marine spatial planning and blue economy strategies means expanding our definitions of value—beyond economic output and biodiversity metrics—to include meaning, memory, beauty, access, and identity.

This calls for:

-

Interdisciplinary teams involving planners, artists, ecologists, community leaders, and Indigenous elders.

-

Narrative and visual methods, such as storytelling, speculative design, ethnography, and mapping of emotional geographies.

-

Policy tools that recognize cultural seascapes, aesthetic conservation zones, and blue heritage corridors.

The ocean is not just a container for activities—it is a living, storied, and sensorial space that shapes who we are. If marine planning is to be sustainable and just, it must recognize the cultural, aesthetic, and experiential dimensions of marine space as core to design, not peripheral. These dimensions provide the emotional and ethical foundations for the blue economy—making it not only productive but meaningful.

As the world grapples with the intertwined crises of climate change, biodiversity loss, and unsustainable development, the blue economy has emerged as a crucial framework for fostering sustainable growth in ocean and coastal areas. Defined broadly, the blue economy encompasses the sustainable use of ocean resources for economic growth, improved livelihoods, and ocean ecosystem health. However, realizing this vision requires not only policy and scientific innovation but also a fundamental redesign of how we interact with, inhabit, and shape marine and coastal environments.

This is where design, planning, and architecture—including urban designers, marine spatial planners, infrastructure developers, and landscape and seascape architects—play an essential role. These disciplines are uniquely positioned to integrate cultural, ecological, and spatial knowledge, mediating between human activity and natural systems to create resilient, adaptive, and inclusive coastal and oceanic futures.

1. Integrating Coastal and Marine Spatial Planning

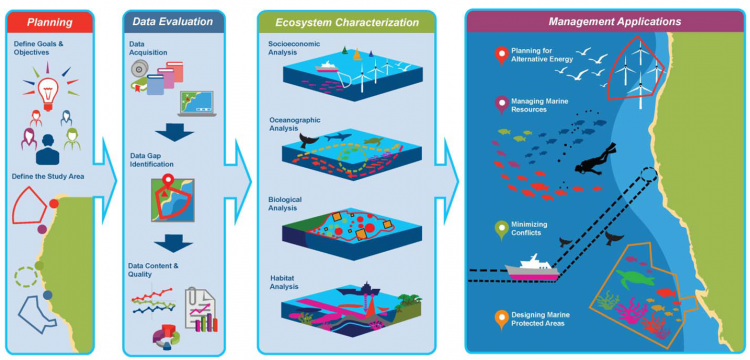

Coastal and Marine Spatial Planning - (Source: coastalscience.nooa.gov)

NCCOS’s Biogeographic Assessment Framework to support marine spatial planning. A logical sequence of steps in information synthesis: 1) talking with managers to determine priorities; 2) assessing the data and identifying data gaps; 3) characterizing the ecosystem patterns and processes including human activities across the area of interest; and 4) working with managers to support specific management applications.

Coastal and marine spatial planning (CMSP or MSP) is a forward-thinking governance tool that organizes human activities in ocean and coastal spaces to reduce conflicts, enhance sustainability, and protect ecosystems. Traditionally driven by regulatory agencies and marine scientists, MSP has recently begun to evolve through collaborations with designers, landscape architects, and spatial planners. These interdisciplinary approaches allow for a more holistic spatial logic—considering not only resource extraction or conservation, but also visual, social, and cultural dimensions of space.

Effective integration of design principles in MSP can lead to dynamic planning that incorporates ecological modelling, socio-economic mapping, visual storytelling, and even public participation through immersive GIS tools. It redefines oceans not just as resource zones but as spaces of heritage, identity, and future-making.

Example: Smart Ocean Planning Initiative (U.S. Northeast)

The Smart Ocean Planning initiative—part of the Northeast Ocean Plan (USA)—is a prime example of an integrated, design-sensitive approach to marine spatial planning. This collaborative process brought together a coalition of stakeholders including state and federal agencies, tribal nations, fishers, offshore wind developers, environmental NGOs, and coastal communities.

The planning process used advanced ecological modelling and spatial data visualizations to map sensitive habitats, migratory pathways (such as those of whales and sea turtles), fishing grounds, and renewable energy corridors. These were visualized via the Mid-Atlantic Ocean Data Portal, a public GIS tool allowing users to explore overlapping layers of ecological and economic activity.

Design professionals contributed by creating intuitive, interactive maps and public engagement tools that translated scientific data into understandable visual stories. The process enabled policymakers to reduce spatial conflicts, such as between offshore wind energy and commercial fishing, while protecting marine biodiversity.

“Good planning isn’t about drawing lines on water—it’s about negotiating values, livelihoods, and ecosystems. Design makes this visible.” — Whitney Tome, former Executive Director, Green 2.0, and member of the Ocean Planning Advisory Group

2. Sustainable Port and Infrastructure Development

Ports and waterfront infrastructure are crucial engines of the blue economy. They serve as gateways for global trade, maritime industries, and coastal urbanization. However, traditional port development has often come at a steep environmental cost—altered hydrology, destroyed wetlands, increased pollution, and climate vulnerability.

Design, architecture, and ecological engineering offer powerful alternatives. Through green infrastructure, adaptive design, and nature-based solutions, ports can be reimagined not just as industrial nodes but as climate-resilient, multifunctional spaces that support both economic and ecological health. Future-ready port infrastructure emphasizes flexibility, biodiversity integration, and community engagement.

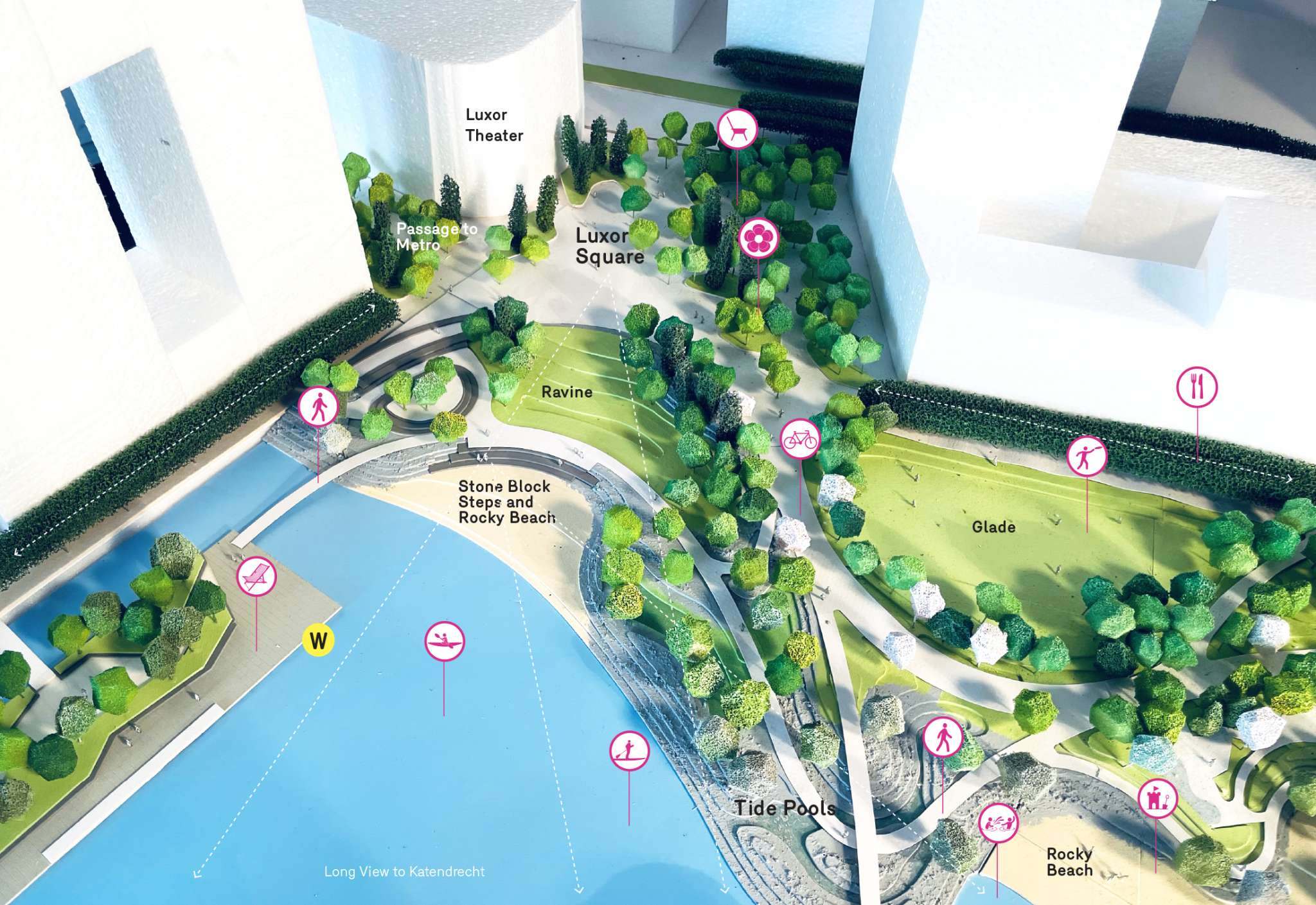

Example: Port of Rotterdam’s “Rijnhaven Park”

Port of Rotterdam's Rijnhaven Park by Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates Inc (Source: mvvainc.com)

In the heart of Europe’s largest port, the Port of Rotterdam’s Rijnhaven Park is a flagship example of sustainable transformation. What was once a degraded industrial dock is being reimagined as a vibrant urban waterpark combining floating architecture, tidal ecosystems, and public waterfront space.

The project includes:

-

Floating pavilions and parks that adjust to changing sea levels.

-

Tidal gardens and habitat islands that restore estuarine ecology.

-

Integration of stormwater retention systems and natural cooling strategies for urban heat mitigation.

-

Public boardwalks, cultural programming spaces, and biodiversity corridors that reconnect residents with their water heritage.

Port of Rotterdam's Rijnhaven Park (Source: mvvainc.com)

The design was led by De Urbanisten, a Dutch urban design firm known for climate-adaptive architecture, and involved collaborations between the municipality, port authorities, and ecological scientists.

“Rijnhaven demonstrates that ports can be public, poetic, and performative—blending infrastructure with life-supporting systems.” — Trudi van der Elsken, Project Architect at De Urbanisten

Port of Rotterdam's Rijnhaven Park (Source: matthijshollanders.com)

3. Landscape and Seascape Architects as Mediators of Cultural and Ecological Values

While engineering and planning are often concerned with technical and regulatory functions, landscape and seascape architecture focus on crafting spaces that embody memory, meaning, and multispecies relationships. These professionals have long worked at the edge of ecology and aesthetics, interpreting land- and seascapes through a cultural lens.

In the context of the blue economy, they serve as critical mediators—weaving together ecological restoration, Indigenous knowledge, recreational needs, and climate adaptation into cohesive spatial narratives. These designers are equipped to interpret invisible forces, such as tides, sediment flows, or ancestral sea routes, and give them material and visual form.

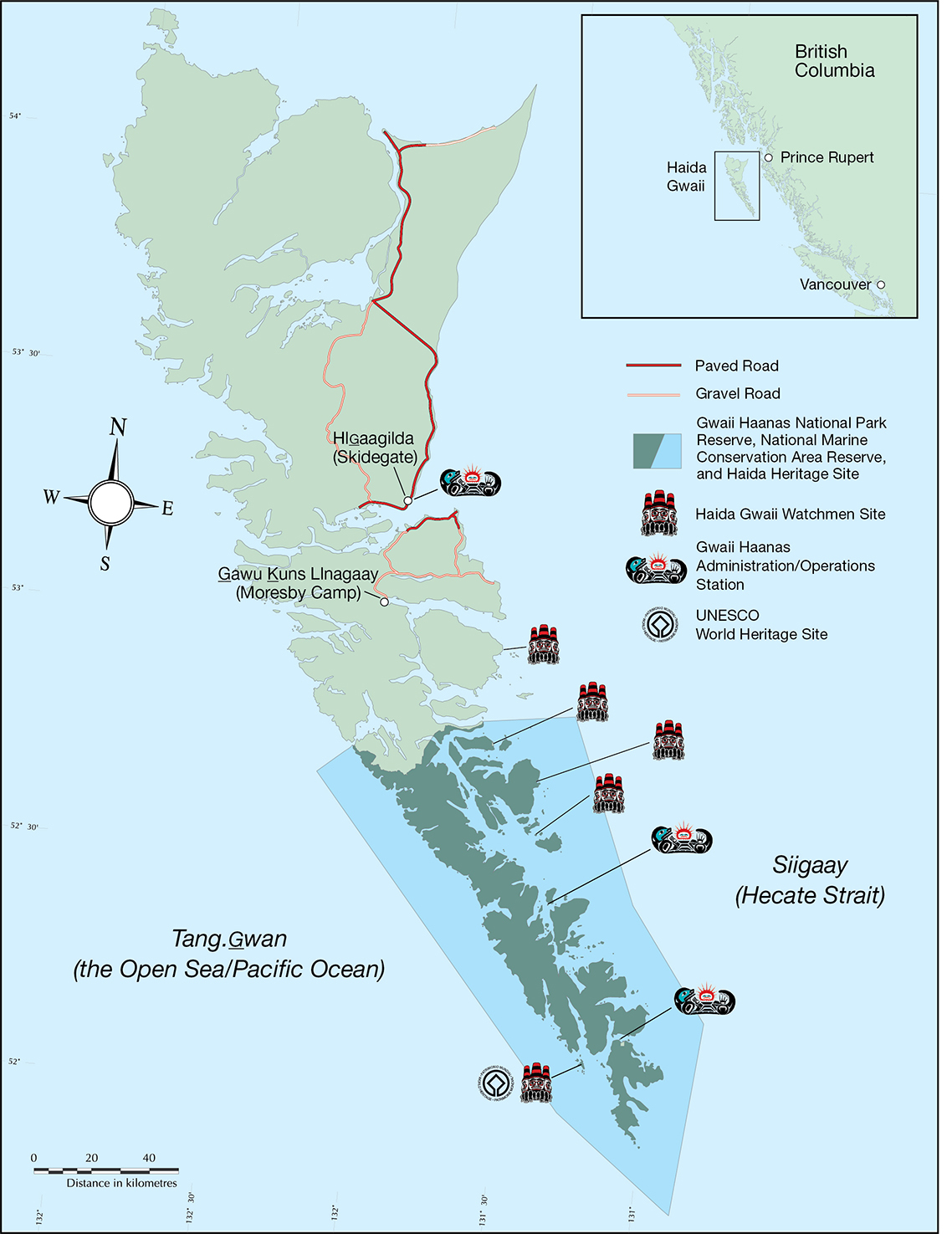

Example: Haida Gwaii Marine Plan (Canada)

Haida Gwaii Marine Plan (Sorce: parks.canada.ca)

Located off British Columbia’s north coast, the Haida Gwaii archipelago is a biologically rich and culturally sacred territory of the Haida Nation. The Haida Gwaii Marine Plan, developed jointly by the Council of the Haida Nation and the Province of British Columbia, is a paradigm-shifting effort that blends Indigenous governance, marine ecology, and landscape-scale planning.

The plan:

-

Establishes marine protection areas co-managed by Haida stewards.

-

Prioritizes cultural seascapes, such as traditional fishing areas, sacred ocean sites, and historical sea routes.

-

Applies Haida traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) alongside scientific studies.

-

Proposes low-impact marine tourism and seaweed aquaculture as sustainable development paths.

-

Uses visual storytelling (maps, drawings, oral narratives) to articulate ancestral relationships with marine territory.

Seascape architects and visual planners collaborated with Haida communities to create aesthetic frameworks and spatial stories that represent both ecological values and Indigenous worldviews.

“This plan speaks in the language of the sea and the ancestors—it is a vision that lives beyond extractive timelines.” — Guujaaw, Hereditary Chief and former President of the Haida Nation

Example: Sydney’s Living Seawalls

Sydney's Living Seawalls (Source: reefdesignlab.com - livingseawalls.com.au)

In cities like Sydney, where urbanization meets the ocean, hard seawalls have historically replaced natural habitats, creating marine deserts. The Living Seawalls project, led by researchers at the University of New South Wales and designed in partnership with marine ecologists and industrial designers, rethinks seawalls as habitat scaffolds.

Using 3D-printed modular panels designed to mimic the textures and complexity of natural rock pools and oyster beds, these seawalls:

-

Increase microhabitat diversity, supporting over 85 marine species including fish, seaweed, and mollusks.

-

Demonstrate a 36% boost in biodiversity compared to traditional flat seawalls.

-

Serve as public education spaces, turning infrastructure into living classrooms.

The design blends ecological science, industrial design, and public art—positioning cities as stewards of the ocean.

“This is not just a wall—it’s a conversation with nature, and with the future of coastal cities.” — Dr. Melanie Bishop, Project Lead, Living Seawalls

Featured Posts

Blog Topics

Urban environment & Public spaces

Stay updated with the latest articles and insights from The Landscape Lab. Here, you will find valuable information and engaging content.

Waterfront & Coastal Resilience

Stay updated with the latest articles and insights from The Landscape Lab. Here, you will find valuable information and engaging content.

Captivating Photography

Stay updated with the latest articles and insights from The Landscape Lab. Here, you will find valuable information and engaging content.

Why Read The Landscape Lab Blog?

The way we design and interact with landscapes is more important than ever. As cities expand, coastlines shift, and climate change reshapes our world, the choices we make about land, water, and urban spaces have lasting impacts. The Landscape Lab Blog is here to spark fresh conversations, challenge conventional thinking, and inspire new approaches to sustainable and resilient design.

If you’re a landscape architect, urban planner, environmentalist, or simply someone who cares about how our surroundings shape our lives, this blog offers insights that matter. We explore the intersections between nature and the built environment, diving into real-world examples of cities adapting to rising sea levels, innovative waterfront designs, and the revival of native ecosystems. We look at how landscapes can work with nature rather than against it, ensuring long-term sustainability and biodiversity.

By reading The Landscape Lab, you'll gain a deeper understanding of the evolving field of landscape design—from rewilding initiatives to regenerative urban planning. Whether it’s uncovering the forgotten history of resilient landscapes, analyzing groundbreaking projects, or discussing the future of green infrastructure, this blog provides a space for learning, inspiration, and meaningful dialogue.

Location:

The Landscape Lab

123 Greenway Drive

Garden City

NY 12345

United Kingdom

Contact Number:

Get in Touch:

contact@thelandscapelab.co.uk

© 2025 thelandscapelab.co.uk - Your go-to blog for landscaping insights