While the Blue Economy holds immense promise as a model for regenerative and sustainable development, its long-term success hinges on navigating a range of critical environmental, governance, and social equity challenges. As global interest in ocean-based economic growth intensifies, so too does the urgency to ensure it does not come at the expense of ocean health, biodiversity, and the rights of local communities.

Overfishing, Ocean Acidification, and Marine Pollution

Source: thenewlede.org

Overfishing remains one of the most pressing threats to marine ecosystems. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) reports that over 34% of global fish stocks are now being exploited beyond sustainable limits, threatening food security, biodiversity, and livelihoods in coastal regions. Unsustainable practices such as bottom trawling and illegal fishing damage habitats and deplete species at a pace faster than they can replenish.

Example: In Senegal, industrial overfishing by foreign trawlers has depleted nearshore stocks, forcing local artisanal fishers to venture farther offshore at greater personal and ecological risk (Greenpeace, 2021).

Senegal Fishermen - Source: Simonetta Pugnaghi_unsplash

Landscape Architecture & Urban Planning Response:

Designers can advocate for marine spatial planning (MSP) that zones for ecological regeneration alongside human use. Coastal green infrastructure—such as oyster reefs or mangrove buffers—can help restore fish habitats and improve water quality.

Ocean acidification is another growing concern, driven by increased atmospheric CO₂ absorption by the oceans. Since the industrial revolution, ocean acidity has increased by about 30%, reducing the ability of shell-forming organisms like corals, oysters, and plankton to thrive. This has cascading effects on food webs and marine ecosystems crucial to economic sectors like fisheries and tourism.

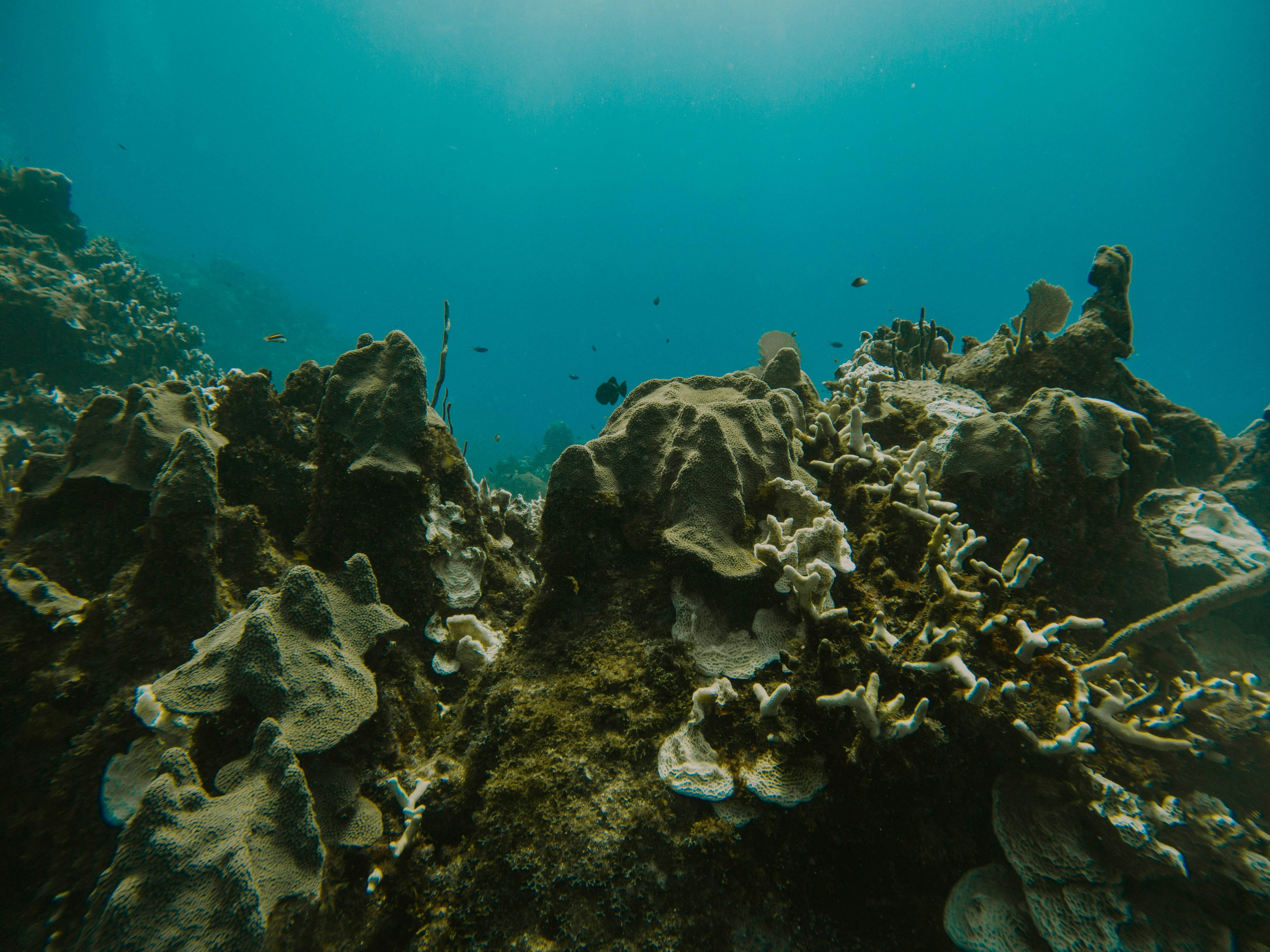

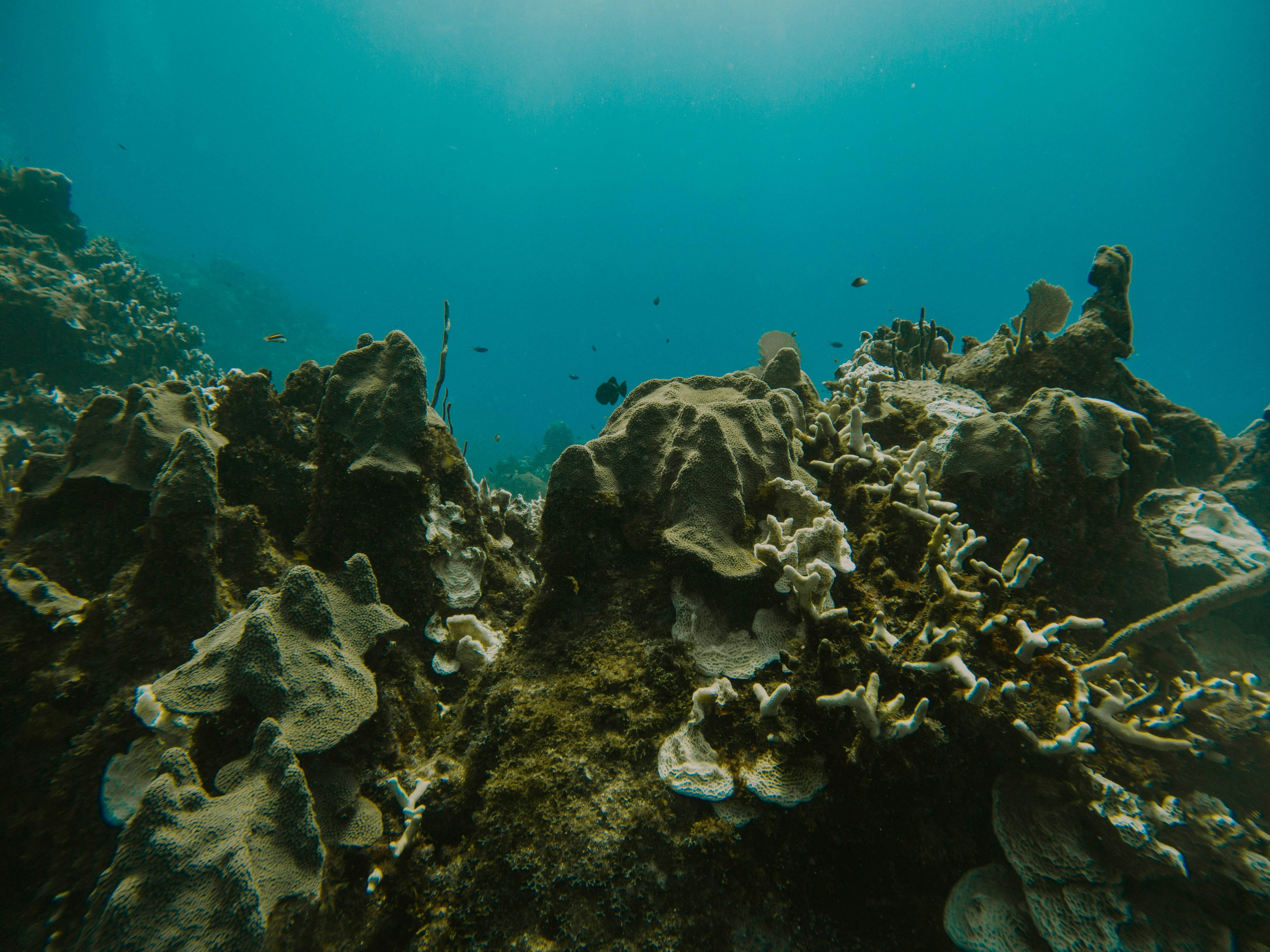

Ocean Acidification - Source: Conner Baker_unsplash

Example: In Palau, acidification is contributing to coral bleaching, threatening tourism, fisheries, and shoreline protection (UNESCO, 2021).

Design Response:

Landscape architects can incorporate nature-based solutions (NbS) such as coral gardening, eelgrass meadows, and shellfish restoration into coastal design strategies to buffer ocean acidity and regenerate marine ecosystems.

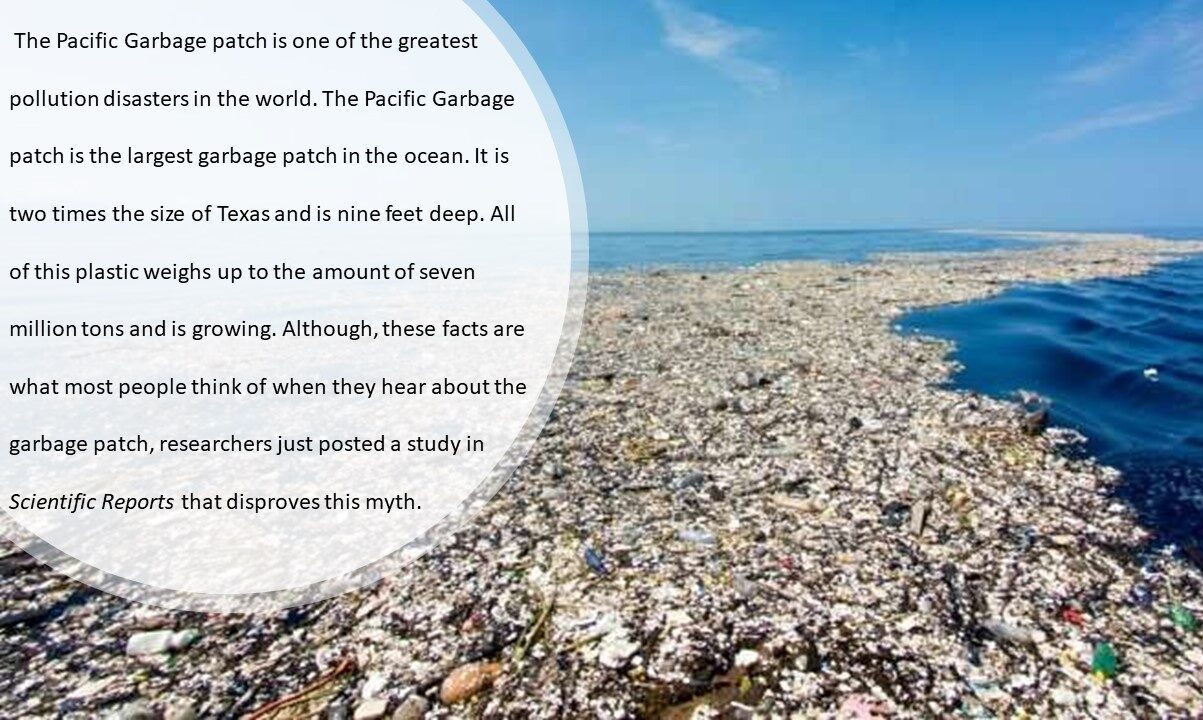

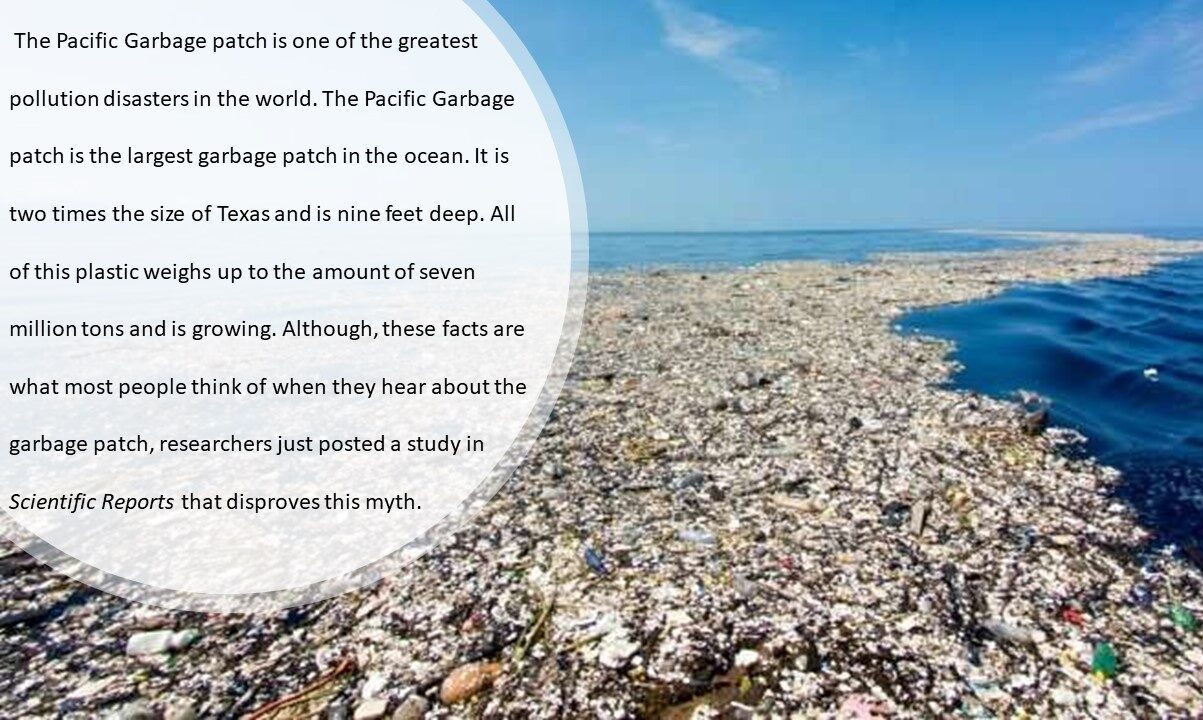

Marine pollution—especially plastic waste—is choking marine life and ecosystems. An estimated 11 million metric tons of plastic enter the ocean annually, according to the Pew Charitable Trusts. Microplastics have now been found in the deepest ocean trenches and in seafood consumed by humans. Chemical runoff from agriculture and untreated sewage also contribute to harmful algal blooms and "dead zones" where marine life cannot survive.

Example: The Gulf of Thailand sees up to 3 million plastic bags enter its waters daily, damaging fishing equipment and harming marine life.

Source: Naja Bertolt Jensen_unsplash.com

Design Response:

Urban planners can help by improving stormwater systems, introducing plastic bans, designing waste capture wetlands, and supporting circular waste economies that prevent leakage into marine systems.

Case in Point: The Great Pacific Garbage Patch, covering an area estimated to be twice the size of Texas, exemplifies the scale of marine plastic pollution and the challenge of cleaning up legacy waste.

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch - Source: planetforward.org

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch Map - Source: americanoceans.org

Marine Resource Governance and Illegal Activities

Weak governance and jurisdictional gaps in international waters complicate efforts to manage marine resources sustainably. Over 60% of the ocean lies beyond national boundaries, governed by a fragmented patchwork of legal frameworks. While frameworks like UNCLOS and the Port State Measures Agreement exist, enforcement is weak, and emerging sectors (e.g., deep-sea mining) are poorly regulated. The lack of a comprehensive and enforceable global ocean governance mechanism enables unsustainable exploitation and illegal activities.

Example: The Clarion-Clipperton Zone in the Pacific is being eyed for mining rare metals, with limited ecological assessments or protections (Deep Sea Conservation Coalition, 2023).

Design Response:

Urban coastal regions can serve as policy laboratories for testing MSP, integrated governance, and participatory planning models—building partnerships between governments, Indigenous communities, scientists, and designers.

Destruction of the illegal cargo of the Fu Yuan Yu Leng in Galapagos National Park - Source: mongabay.com

Illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing is estimated to account for up to 26 million tons of fish annually—worth over $23 billion—and disproportionately affects developing nations with limited enforcement capabilities. It undermines legitimate fisheries, depletes fish stocks, and can be linked to other crimes such as human trafficking and labor exploitation.

Example: In Ghana, “saiko” fishing (illegal transshipment at sea) has depleted stocks and destabilized local economies (Environmental Justice Foundation, 2021).

Design Response:

Ports can be redesigned as transparent, traceable nodes in sustainable seafood supply chains. Landscape architects can integrate education hubs and community-led monitoring within working waterfronts.

Despite international agreements such as the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and FAO’s Port State Measures Agreement, enforcement remains inconsistent. The challenge is further amplified in areas like deep-sea mining, where regulation is still evolving despite growing environmental concerns.

Example: In West Africa, small island nations like Cabo Verde and Guinea-Bissau struggle to monitor illegal industrial fishing fleets operating within their exclusive economic zones (EEZs), costing them millions in lost revenue annually.

Equity Issues: Access and Benefit-Sharing Between Nations and Communities

While the Blue Economy offers new economic opportunities, its benefits are not always equitably shared. Small Island Developing States (SIDS) and coastal Indigenous communities, despite being custodians of rich marine ecosystems, often lack the financial resources, technological capacity, or bargaining power to capitalize on the blue economy or defend their rights.

There are growing concerns about “blue grabbing”—a term describing how powerful private or state actors gain control over marine resources in ways that displace traditional users and exclude local communities. Examples include the privatization of fishing rights, marine ecotourism monopolies, and offshore energy development that bypasses community consultation.

Example: Large-scale marine tourism developments in Zanzibar have displaced fishing villages, while foreign investors reap most profits (Blue Ventures, 2020).

The 411 hectare resort will be developed in seven phases along 4km of Indian Ocean coastline - Source: Zanzibar Amber Resort

Design Response:

Landscape architects and planners can support co-managed marine protected areas and community-based ecotourism that retain cultural integrity and redistribute benefits locally.

Access and benefit-sharing (ABS) mechanisms must be part of international and national Blue Economy strategies. These mechanisms ensure that traditional knowledge holders and frontline communities have:

-

A seat at the decision-making table,

-

Legal recognition of customary rights,

-

And fair compensation when their resources are commercially utilized.

Example: The Nagoya Protocol, though more commonly applied to land-based genetic resources, offers a framework for marine benefit-sharing. Some Pacific Island nations are now exploring how to adapt it to ocean biodiversity.

Example: The Pacific nation of Kiribati is exploring legal protections for traditional knowledge tied to marine species used in pharmaceuticals.

Design Response:

Designers can advocate for the inclusion of cultural landscapes and traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) in Blue Economy planning—recognizing both tangible and intangible marine heritage.

Conclusion: Navigating Trade-offs for a Just Blue Economy

The Blue Economy is not inherently sustainable or just—it must be intentionally shaped to avoid reproducing the extractive models that have harmed our oceans in the past. Addressing overfishing, pollution, and climate change must go hand-in-hand with reforms in governance and equity.

By investing in community-led marine management, strengthening international cooperation, and integrating Indigenous and local knowledge systems, we can build a Blue Economy that truly regenerates ecosystems, supports livelihoods, and ensures intergenerational fairness.

Landscape architects and urban planners have a vital role in:

-

Supporting equitable governance of marine spaces

-

Integrating green-blue infrastructure to mitigate environmental pressures

-

Facilitating community-centered coastal development

-

Preserving cultural identity and local access in waterfront regeneration

By engaging deeply with marine systems and the communities who depend on them, built environment professionals can shape the interface between land and sea—where climate, culture, economy, and ecology converge.

References

-

FAO. (2022). The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture.

-

Pew Charitable Trusts. (2020). Breaking the Plastic Wave.

-

NOAA. (2021). Ocean Acidification: Fast Facts.

-

Greenpeace. (2021). Empty Nets: Industrial Fishing in Senegal.

-

Deep Sea Conservation Coalition. (2023). Deep-Sea Mining Primer.

-

EJF. (2021). Stolen at Sea: Saiko Fishing in Ghana.

-

UNESCO. (2021). Coral Reefs and Climate Change.

-

Blue Ventures. (2020). Community-Led Marine Conservation in the Western Indian Ocean.

Source cover picture: worldwildlife.org