“As the seas rise, so too must our imagination.” — Kate Orff, SCAPE Landscape Architecture

1. A World in Flux: Climate Change and the Vulnerability of Coasts

For centuries, proximity to the sea was a strategic advantage. Coastal cities were gateways to trade, engines of economic growth, and magnets for migration. But today, what was once a blessing is becoming a looming threat. Climate change is rewriting the rules. Sea levels are rising, storms are intensifying, and once-stable shorelines are eroding away.

According to the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report, global sea levels could rise by up to one meter by the end of the century—threatening over 680 million people living in low-lying coastal zones. But beyond the science and the statistics lies a fundamental question: How should we respond? Should we fight back—or learn to live differently?

2. How Can Coastlines Prepare for Climate Change?

Preparing our coastlines for climate change is not just about erecting barriers—it’s about reimagining our relationship with the edge. In the past, we’ve responded to rising seas with blunt-force infrastructure: concrete seawalls, steel bulkheads, tidal gates. These defensive structures have often served their purpose in the short term—but they come with limitations. They’re expensive to build and maintain, ecologically disruptive, and often create a false sense of security, encouraging development in high-risk zones.

Coastal seawall (Source: milbank.co.uk) Steel bulkhead (Source: kitzenconstruction.com)

To face the climate challenges ahead, we must shift from reactive defense to proactive adaptation.

This means moving beyond the “fortress mentality” to embrace strategies that are:

-

Flexible — able to adjust as sea levels rise or as storm patterns shift.

-

Adaptive — designed to evolve with ecological, climatic, and social change.

-

Inclusive — developed with local communities, not imposed upon them.

In other words, preparing our coasts isn’t about winning a battle against nature; it’s about learning to live with water—working with natural systems, not against them.

Take the example of Rotterdam, a city that lies largely below sea level. Instead of hiding from its watery reality, Rotterdam has chosen to embrace water as a civic asset. Through initiatives like the Water Squares—public plazas that double as rainwater reservoirs—the city is turning flood risk into an opportunity for public life. “We can’t escape the water,” says Dutch urban designer Fransje Hooimeijer, “so we make space for it.”

Water square Benthemplein - Rotterdam, Neatherland: it is public space and storm water storage combined in one space. The square is part of a strategy to increase climate resilience by adaptive measures. (Source:urbanisten.nl_Ossip van Duivenbode)

Water square Benthemplein - Rotterdam, Neatherland (Source:urbanisten.nl_Jurgen Bals)

Preparation also demands a rethink of how cities interface with water. This means reshaping urban form—building floodable parks, elevating infrastructure, restoring natural buffers like wetlands and dunes. But it also means designing for beauty and culture, not just functionality. Too often, resilience is seen as a technical problem; but it’s equally a question of identity and belonging.

Floodable Rodney Cook Sr. Park - Atlanta, Georgia, USA: Seamlessly integrating functional green engineering features, the park can alleviate flooding (Source: hdrinc.com_Paul Dingman)

Why should coastal protection be ugly or alienating? Why not create waterfronts that inspire connection, tell local stories, or restore lost ecologies?

In Singapore, for example, the Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park was transformed from a concrete drainage canal into a meandering natural river with floodplains and lush vegetation. The project not only improved flood control—it created a beloved public space, enhanced biodiversity, and reconnected people to nature in the heart of the city.

Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park - Singapore: the park integrated multi-functional design promotes a sustainable balance between the need for effective stormwater management, a healthy site ecosystem and pleasurable urban spaces (Source:dreiseitlconsulting.com)

Critically, none of these solutions work in isolation. Real preparation requires balancing competing priorities—the safety of homes and critical infrastructure, the health of coastal ecosystems, the vitality of local economies, and the cultural narratives that define a place.

To do this, long-term investment is essential—not just in infrastructure, but in governance, education, and community capacity. Local voices must be heard and integrated throughout the design and implementation process. The coast is not a blank slate—it’s someone’s home, someone’s livelihood, someone’s memory.

Ultimately, preparing for climate change is not about resisting change—it’s about designing change wisely. By embracing complexity, we can create coastlines that are not only safer, but also more alive, more just, and more connected to the people who depend on them.

3. Designing Coastal Adaptation Strategies: From Protection to Transformation

As seas rise and storms intensify, the question isn’t whether coastal communities should adapt—it’s how. Designing adaptation strategies for our coasts is about more than just holding the line. It’s about choosing wisely between protection, accommodation, and retreat—and, increasingly, transforming how we live at the water’s edge.

Three Core Adaptation Pathways

Adaptation strategies typically fall into three primary categories:

1. Protect (e.g., seawalls, levees, breakwaters):

This is the most familiar response—building physical barriers to keep water out. Seawalls, levees, and breakwaters have long been the go-to tools in our coastal defence arsenal. They’re often seen as “hard” solutions—engineered systems that create a clear boundary between land and sea. In places like Venice, the MOSE flood barrier system exemplifies high-tech protection, aiming to shield the historic city from ever-higher tides. However, protective structures come at a high financial cost and can sever the natural relationship between land, water, and ecological systems.

2. Accommodate (e.g., elevating buildings, floodable zones):

Rather than fight water, accommodation strategies accept its presence and design around it. This might mean elevating homes on stilts, constructing amphibious housing that can float during floods, or creating floodable public spaces. The Netherlands’ “Room for the River” programme is a standout example—redesigning riverbanks to allow controlled flooding in designated areas, reducing pressure on urban zones and restoring ecological function. The key here is flexibility: allowing water in, but on our terms.

3. Retreat (e.g., managed relocation):

The most controversial—yet sometimes necessary—strategy involves moving people and assets out of harm’s way. Managed retreat asks hard questions: when is it no longer viable—or ethical—to rebuild in place? In some areas of New York and New Jersey, post-Hurricane Sandy buyout programs helped residents in high-risk zones relocate, turning flood-prone land back into wetlands. It’s not just a last resort—it can also be a visionary act of renewal, if done with community dignity, long-term planning, and environmental goals in mind.

Beyond Categories: The Rise of Hybrid Strategies

In recent years, climate and design experts have begun to move beyond rigid categories. The most effective approaches aren’t strictly protective, accommodative, or retreat-based—they’re often a hybrid, blending grey infrastructure (like levees or pumps) with green or nature-based solutions (like restored marshes or oyster reefs).

This shift is driven by both necessity and possibility. Climate uncertainty demands flexibility, and hybrid solutions offer multiple co-benefits: risk reduction, ecological restoration, public amenity, economic revitalisation, and cultural reconnection.

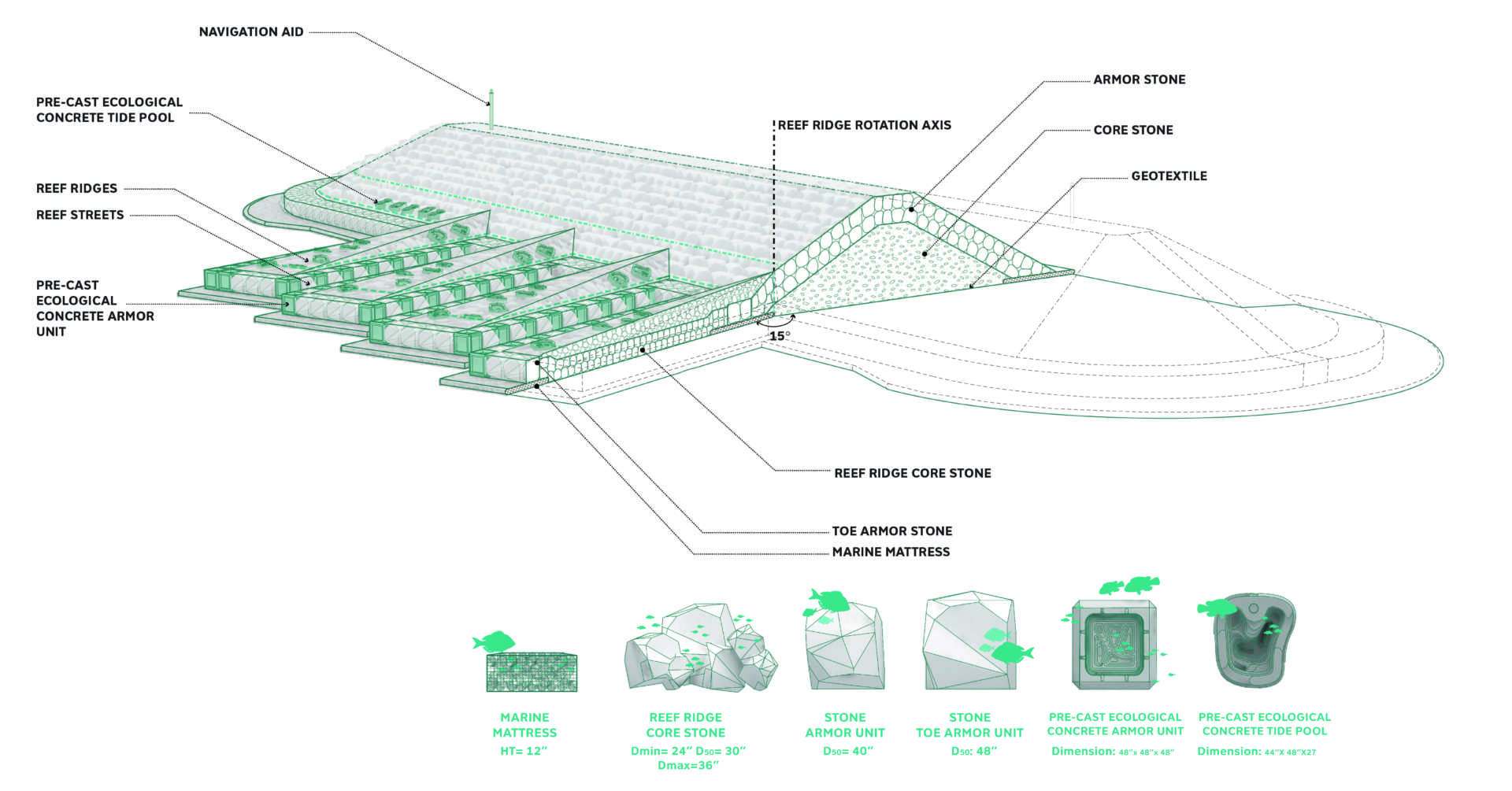

Take the visionary Living Breakwaters project by SCAPE Landscape Architecture off the coast of Staten Island, New York.

After Superstorm Sandy devastated Staten Island in 2012, it became clear that conventional coastal defences had failed to protect communities. The area suffered severe erosion, flooding, and loss of life.

SCAPE Landscape Architecture, led by Kate Orff, proposed a visionary solution—"Living Breakwaters." Rather than a conventional seawall, the team designed a series of ecologically-enhanced breakwaters that attenuate wave energy while supporting marine habitat, improving water quality, and fostering youth education and stewardship. The breakwaters provide physical protection—but they also offer social and ecological resilience, fostering a new relationship between people and the shoreline.

Living Breakwaters - Staten Island, NYC, USA

The project consists primarily of 2,400 linear feet of near-shore breakwaters—partially submerged structures built of stone and ecologically-enhanced concrete units—that break waves, reduce erosion of the beach along Conference House Park, and provide a range of habitat spaces for oysters, fin fish and other marine species.

Living Breakwaters - Staten Island, NYC, USA

Beyond the physical breakwaters, the project aims to build social resilience in Tottenville through educational programs for local schools in partnership with the Billion Oyster Project (BOP), as well as years of engagement through the Citizens’ Advisory Committee (CAC), a coalition of local stakeholders.

What makes this project special is its multi-benefit approach: it’s not just a buffer—it’s a regenerative system that fosters oyster reefs, improves biodiversity, and provides educational and recreational spaces. It's expected to reduce wave heights by up to 70% during storms, while nurturing a resilient marine environment.

As Kate Orff, founder of SCAPE, explains:

“We’re designing infrastructure that doesn’t just defend—it restores, educates, and connects. It’s about cultivating an intergenerational investment in place, not just building a wall.”

In Vietnam, where over 70% of the population lives along low-lying deltas, the World Bank’s “Resilient Shores” programme takes a hybrid approach as well: building dikes while restoring mangroves, which buffer wave impacts and provide critical ecosystem services. This strategy both protects rural livelihoods and restores natural capital.

From Strategy to Transformation

What emerges from these examples is a powerful insight: coastal adaptation is no longer just a technical or defensive response. It’s an opportunity for transformation—rethinking what it means to live near water in a time of planetary change.

Design plays a pivotal role in this transformation. It allows us to visualise futures that are not just survivable, but desirable. It makes room for dialogue between engineers, ecologists, planners, and communities. It helps us balance values: safety, culture, economy, biodiversity.

And crucially, it reminds us that the most resilient places are not those that resist change—but those that embrace it with creativity, equity, and care.

Wuhan Yangtze Riverfront Park - Wuhan, China (Source: sasaki.com)

Wuhan’s Yangtze Riverfront Park leverages the river’s dynamic flooding to nurture a rich regional ecology, reinforce traditional wisdom and the local identity of living with an ever-changing river, and creates a dynamic recreational experience which is acutely attuned to the seasonal rise and fall of the Yangtze’s waters.

4. Tailoring Responses to Local Realities: One Shoreline Does Not Fit All

When it comes to climate adaptation, there is no universal blueprint as coastal challenges vary dramatically.

Each stretch of coastline is shaped by a distinct blend of geography, ecology, culture, economy, and history. A remote fishing hamlet in Indonesia faces entirely different pressures than a bustling commercial port in Rotterdam or a public waterfront in Toronto. What binds them, however, is a shared exposure to rising seas—and the need for context-sensitive, community-driven solutions.

That’s why coastal resilience planning must move beyond copy-paste models and lean into tailored, place-based responses. These strategies acknowledge local realities rather than override them, ensuring that adaptation is not only technically sound, but also socially relevant, culturally respectful, and ecologically aligned.

Case Study: Porthcawl, Wales — Weaving Safety with Sense of Place

Sandy Bay - Porthcawl, Wales: Restoring flood defences, enhancing biodiversity and managing coastal risk (Source: arup.com)

On the coast of South Wales lies Porthcawl, a small seaside town with a rich maritime history and a once-thriving tourism economy. By the early 2010s, Porthcawl was facing a compound set of challenges. Its coastal defences were aging and increasingly inadequate in the face of intensifying storms. The town’s economy had dwindled, tourism was declining, and the risk of flooding loomed large over the residential areas near Sandy Bay.

The town could have responded with a standard seawall upgrade—but instead, it chose to embrace a holistic, risk-based design strategy. The goal was not only to reduce flood risk, but to revitalize the coastline, restore its ecological function, and reconnect the community with its identity.

Led by Bridgend County Borough Council and supported by environmental and engineering consultants, the Sandy Bay Coastal Risk Management Scheme emerged as a multi-benefit intervention. Here's how the transformation unfolded:

-

Flood Protection, Reimagined: The project didn’t just raise barriers; it redesigned them into a community asset. The upgraded sea defenses were integrated into a vibrant promenade, creating a safe, accessible public realm while protecting over 700 properties from future flooding.

-

Dune Restoration: Rather than replacing eroded dunes with hard infrastructure, the project invested in restoring natural dune systems to act as buffers. This allowed nature to do what it does best—absorb wave energy, protect inland areas, and foster biodiversity.

-

Heritage Conservation and Public Amenities: The town’s historic breakwater, once under threat, was preserved. New pedestrian paths, seating, and interpretive signage celebrated the town’s seafaring past, inviting both residents and visitors to reengage with the coast.

-

Community Co-Creation: Crucially, the project was not imposed from above. Community consultation was built into the design process, ensuring that locals shaped the vision and outcomes. This made the changes not only more effective but more meaningful. As one town council member noted during the process, “Flood walls alone don’t make people feel safe—being part of the solution does.”

The result? A resilient, reimagined coastline—where environmental protection and economic revitalisation go hand in hand, and where identity isn’t sacrificed in the name of adaptation, but strengthened by it.

Global Resonance, Local Nuance

Porthcawl’s story reflects a growing recognition in coastal adaptation: resilience must be rooted in local reality. The same principle can be seen around the world:

-

In Semarang, Indonesia, communities are responding to land subsidence and sea level rise by rebuilding mangroves and developing stilt housing, drawing from indigenous knowledge while introducing modern construction methods.

-

In Toronto, Canada, the Don Mouth Naturalization project is transforming a formerly industrial riverside into a climate-resilient urban park, integrating flood control with habitat creation, Indigenous consultation, and public use.

-

In Rotterdam, one of Europe’s most climate-forward cities, adaptation strategies include not just sophisticated storm barriers, but also floating neighborhoods, water plazas, and sponge gardens—each one carefully designed to reflect the dense, low-lying, and water-rich character of the Dutch delta.

These examples show that technical innovation must be matched by cultural intelligence. The most successful coastal strategies are those that listen—deeply—to the people who call these places home.

Katwijk Coastal Defence - Leiden, The Neatherlands (Source: okra.nl)

The dyke and garage are completely hidden from view by natural-looking dunes. An extensive network of paths has been built to connect village and beach, offering views of the sea. The highlight of the design is a broad dune transition that serves as a welcome space and event plaza, in total forming a vibrant heart for the coast of Katwijk coast.

5. Understanding the Spectrum of Adaptation Strategies

Adapting our coastlines to climate change is not a one-size-fits-all endeavour. The strategies available exist on a spectrum—from traditional, engineered defences to ecologically inspired interventions, and even to transformational shifts in how we occupy land. Each strategy brings with it trade-offs, and selecting the right mix depends on a nuanced understanding of geography, governance, culture, funding, and community priorities.

Let’s unpack the four main types of adaptation strategies, and explore how they’re being applied around the world.

Hard Engineering: Strength in Structure, But at What Cost?

These are the conventional tools of coastal defence: seawalls, levees, dikes, and bulkheads. Built from concrete, steel, or stone, they are designed to hold back the sea, providing immediate and visible protection—especially in densely populated or economically vital areas.

Where It Works:

-

Rotterdam, Netherlands uses some of the world’s most advanced storm surge barriers to protect a city that lies largely below sea level.

-

Venice’s MOSE Project, a system of mobile floodgates, aims to shield the historic city from storm tides.

The Challenge:

While effective in the short term, hard engineering can disrupt coastal ecosystems, accelerate erosion downstream, and create a false sense of security. These structures often require constant maintenance and can be prohibitively expensive for smaller communities.

“If you only build walls, you end up in a box,” said Dutch water management expert Henk Ovink. “Resilience demands a broader vision.”

Nature-Based Solutions: Harnessing the Power of Living Systems

Also called “green infrastructure,” these strategies work with the landscape to absorb wave energy, buffer storm surges, and reduce erosion—while also delivering biodiversity and recreational benefits. Examples include:

-

Mangrove forests, which trap sediment and calm waves.

-

Dune systems, which protect beaches while allowing natural movement.

-

Oyster reefs and salt marshes, which stabilize shorelines and filter water.

Case Study: Vietnam’s Mangrove Belt

In the Mekong Delta, decades of mangrove deforestation left communities exposed to typhoons and saltwater intrusion. Replanting efforts—often led by local women’s groups—have restored vast swathes of coastline. These living buffers not only reduce storm damage but also support fisheries and local livelihoods.

Why It Matters:

Nature-based solutions are more flexible than hard infrastructure, cheaper over time, and carbon-friendly. But they often require space, time to mature, and consistent community stewardship.

Mangroves in Ru Cha, Huong Phong commune, Thua Thien Hue province, Viet Nam (Source: undp.org_Clea Paz-Rivera)

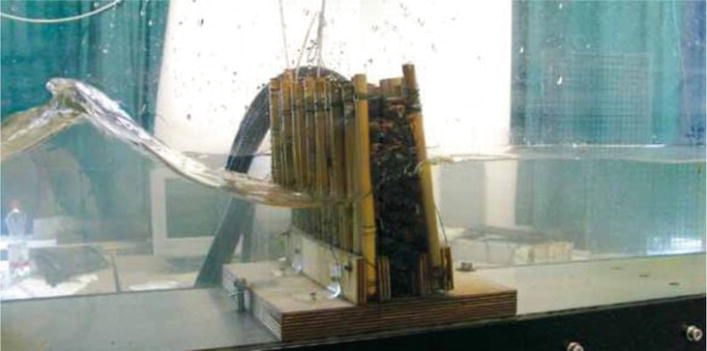

Wave dampening effect of bamboo T-fences, Ca Mau Province, Viet Nam (Source: intechopen.com_R. Sorgenfrei)

Bamboo fences in Khok Kha, Samut Sakhon Province, Thailand (Source: intechopen.com_K. Schmitt)

Physical modelling of wave transmission through bamboo fence, scale 1:20 (Source: intechopen.com_T. Albers).

Hybrid Designs: The Best of Both Worlds

In many places, the most resilient strategy lies in blending grey and green infrastructure. This hybrid approach recognizes that engineering and ecology can work together—not in opposition.

Example: New York’s East Side Coastal Resiliency Project

This $1.45 billion project combines flood walls with raised parklands, stormwater storage, and vegetated berms along the East River. It’s designed not just to protect Lower Manhattan from future storm surges like Hurricane Sandy, but also to create a more beautiful, accessible waterfront.

Hybrid solutions are especially effective in urban environments, where space is limited and stakes are high. They allow cities to layer multiple functions—flood protection, habitat creation, recreation, and more—into a single design.

East Side Coastal Resiliency - NYC, USA (Source: mnlamnlandscape.com)

East Side Coastal Resiliency - NYC, USA (Source: aecom.com)

New shoreline park from the East Side Coastal Resiliency project, near Peter Cooper Village - Stuyvesant Town (Source: New York City Department of Design and Construction_archpaper.com)

Managed Retreat: When Moving Back Is Moving Forward

Perhaps the most controversial—and emotionally charged—strategy is managed retreat: the planned relocation of communities and infrastructure away from high-risk areas. As sea levels rise and storms intensify, some places may become too dangerous or expensive to defend.

Case Study: Isle de Jean Charles, Louisiana

This small island, home to the Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw tribe, has lost 98% of its landmass to coastal erosion and subsidence. With federal and state support, the community is now relocating inland—a complex, ongoing process that raises deep questions about identity, justice, and sovereignty.

Why It’s Hard:

Retreat involves painful trade-offs: leaving ancestral lands, confronting displacement, and managing property rights. Yet in some cases, it may be the most equitable and sustainable path—especially when led by the communities themselves, with adequate resources and cultural sensitivity.

“Retreat doesn’t mean surrender—it means reimagining safety and dignity on our own terms,” says Chief Albert Naquin, a leader of the Isle de Jean Charles Band.

How to Choose? Context Is Everything

Selecting the right strategy—or more often, a combination of strategies—depends on local variables:#

|

Factor |

Considerations |

|

Topography |

Is there room for retreat or restoration? Or are dense urban assets close to the shore? |

|

Socioeconomics |

Who lives there? What are the vulnerabilities and capacities of the community? |

|

Governance |

Are local and national institutions aligned? Are policies adaptive and participatory? |

|

Funding |

Can the project attract investment? Does it deliver co-benefits (economic, ecological, social)? |

In a world of accelerating change, adaptation isn’t a single choice—it’s a process of evolving responses, guided by science, shaped by culture, and grounded in equity.

6. Integrating Climate Risk into Infrastructure and Investment

As climate change accelerates, city-building cannot proceed with yesterday’s assumptions. Flood zones are shifting, droughts are intensifying, and once-in-a-century storms are now arriving every decade—or even more frequently. In this new era, the most resilient cities are those that embed climate risk into every layer of infrastructure and investment decisions—not as an afterthought, but as a guiding principle.

This shift requires moving beyond siloed planning. It means using future climate data to shape everything: zoning laws, energy grids, building codes, insurance models, public transport design, and investment criteria. When climate resilience is woven into the DNA of city planning, it becomes not just a defensive measure—but a competitive advantage.

From Reaction to Resilience: A Whole-Systems Approach

The key is systems thinking. Cities don’t function in isolation—water systems connect to housing, transport links to health care, ports to energy supply. A climate shock in one area can cascade through the entire urban fabric.

Take the example of power infrastructure: in many coastal cities, electrical substations are located in flood-prone areas. A single flood event can leave hundreds of thousands without power, disrupting hospitals, schools, and emergency response. Planning for resilience means elevating or relocating critical systems, using redundant networks, and ensuring that backup power is climate-proof.

“We can no longer treat climate risk as an environmental issue alone,” says Dr. Judy Curry, climate scientist and former chair of the School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences at Georgia Tech. “It is a profound infrastructure challenge—one that affects how we finance, build, and govern our cities.”

Case Study: Cape Town’s City Water Resilience Approach

Few cities have experienced the urgency of climate risk like Cape Town, South Africa, which in 2018 came dangerously close to becoming the first major city to run out of water. “Day Zero”—when the municipal water supply would be shut off—was only narrowly averted through emergency restrictions and public mobilization.

But Cape Town didn’t stop at crisis response. In the aftermath, the city launched the City Water Resilience Approach (CWRA) in collaboration with Arup and the World Resources Institute. The goal: to shift from reactive water management to proactive, integrated resilience planning.

What the CWRA Does:

-

Maps water-related vulnerabilities across the city, from stormwater flooding to drought-prone neighborhoods.

-

Identifies nature-based solutions (NbS) such as wetlands restoration to absorb runoff and recharge aquifers.

-

Aligns multiple stakeholders—utilities, community groups, businesses, and planners—to develop a shared vision.

-

Embeds resilience metrics into budgeting and policy frameworks, ensuring long-term accountability.

Today, Cape Town is not only investing in new desalination and recycling systems but is also restoring key watersheds, integrating green infrastructure into urban planning, and ensuring that water equity—especially in informal settlements—is part of the equation.

“Resilience is not about surviving the next drought,” said Councillor Zahid Badroodien, Cape Town’s Mayoral Committee Member for Water and Sanitation. “It’s about transforming how we value, manage, and govern water for future generations.”

Resilience as a Financial and Policy Imperative

Investors are also waking up to climate risk. Large financial institutions—including the World Bank, BlackRock, and OECD—now call for cities to disclose climate-related vulnerabilities and adaptation plans. Real estate markets increasingly reflect risk-adjusted property values, and insurers are withdrawing from high-risk zones that lack protective infrastructure.

Forward-looking cities are:

-

Embedding climate risk in procurement and capital investment strategies.

-

Creating "resilience bonds" to fund adaptation projects.

-

Partnering with the private sector to align resilience with economic growth.

One example is Boston’s Climate Resilience Checklist, which developers must complete as part of planning approvals. It evaluates exposure to heat, flooding, sea level rise, and ensures new projects contribute to citywide resilience goals.

Why Integration Matters

Embedding climate risk into infrastructure is not about checking a box. It’s about anticipating interconnected disruptions, seizing co-benefits, and building cities that are equitable, beautiful, and durable.

|

Domain |

Climate Resilient Action |

|

Zoning & Land Use |

Limit new development in floodplains; incentivize elevated or amphibious housing |

|

Transport |

Raise roads, build porous surfaces, integrate green corridors |

|

Energy |

Protect substations, invest in distributed solar and battery backup |

|

Water |

Combine gray and green infrastructure for urban drainage |

|

Housing |

Ensure climate adaptation doesn't displace vulnerable communities |

In short, resilience cannot be bolted on. It must be baked in—designed from the beginning, maintained through partnerships partnerships, and scaled through policy.

7. Unlocking Co-Benefits and Economic Potential

When we talk about adapting to climate change, it’s easy to focus on risk: sea level rise, storm surges, erosion, infrastructure failure. But there’s a more hopeful, future-oriented story we often miss. Thoughtful, resilient coastal design doesn’t just protect communities from harm—it unlocks economic vitality, ecological richness, and cultural renewal. When done right, adaptation can actually become an engine for regeneration.

In other words, coastal resilience is not a cost—it’s an investment with multiple returns.

What Are Co-Benefits?

Co-benefits are the additional social, economic, and environmental gains that emerge from climate adaptation strategies. When a seawall doubles as a public promenade, or when a restored marshland becomes a haven for biodiversity and a tourist destination, we are no longer simply mitigating risk—we’re enhancing life.

These projects stimulate:

-

Job creation through construction, restoration, and long-term stewardship.

-

Tourism and place identity, attracting visitors and fostering local pride.

-

Public health improvements, by increasing access to nature, clean air, and active lifestyles.

-

Social equity, by designing with and for communities most impacted by climate risks.

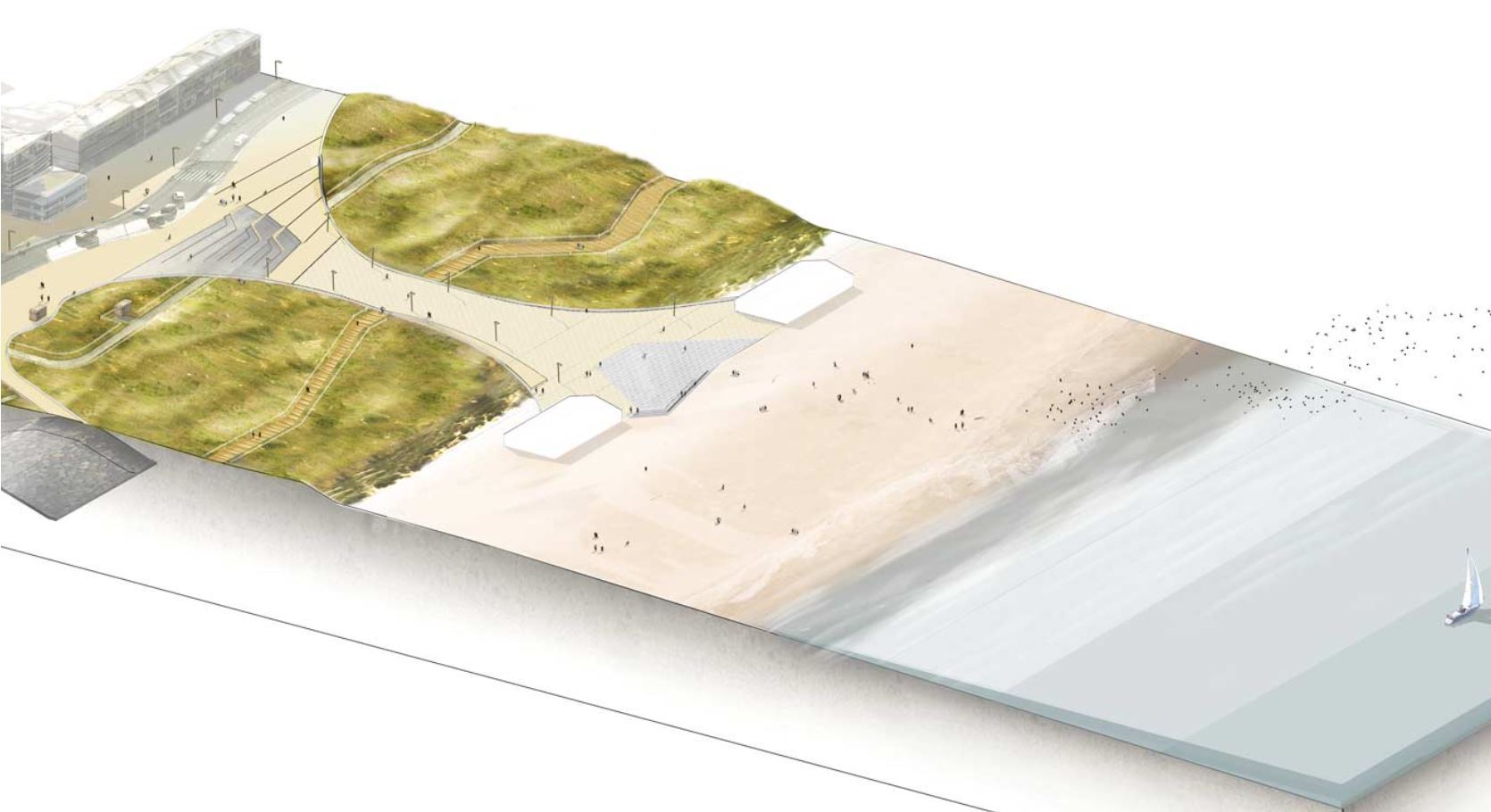

Case Study: Hoboken, New Jersey – Resilience by Design

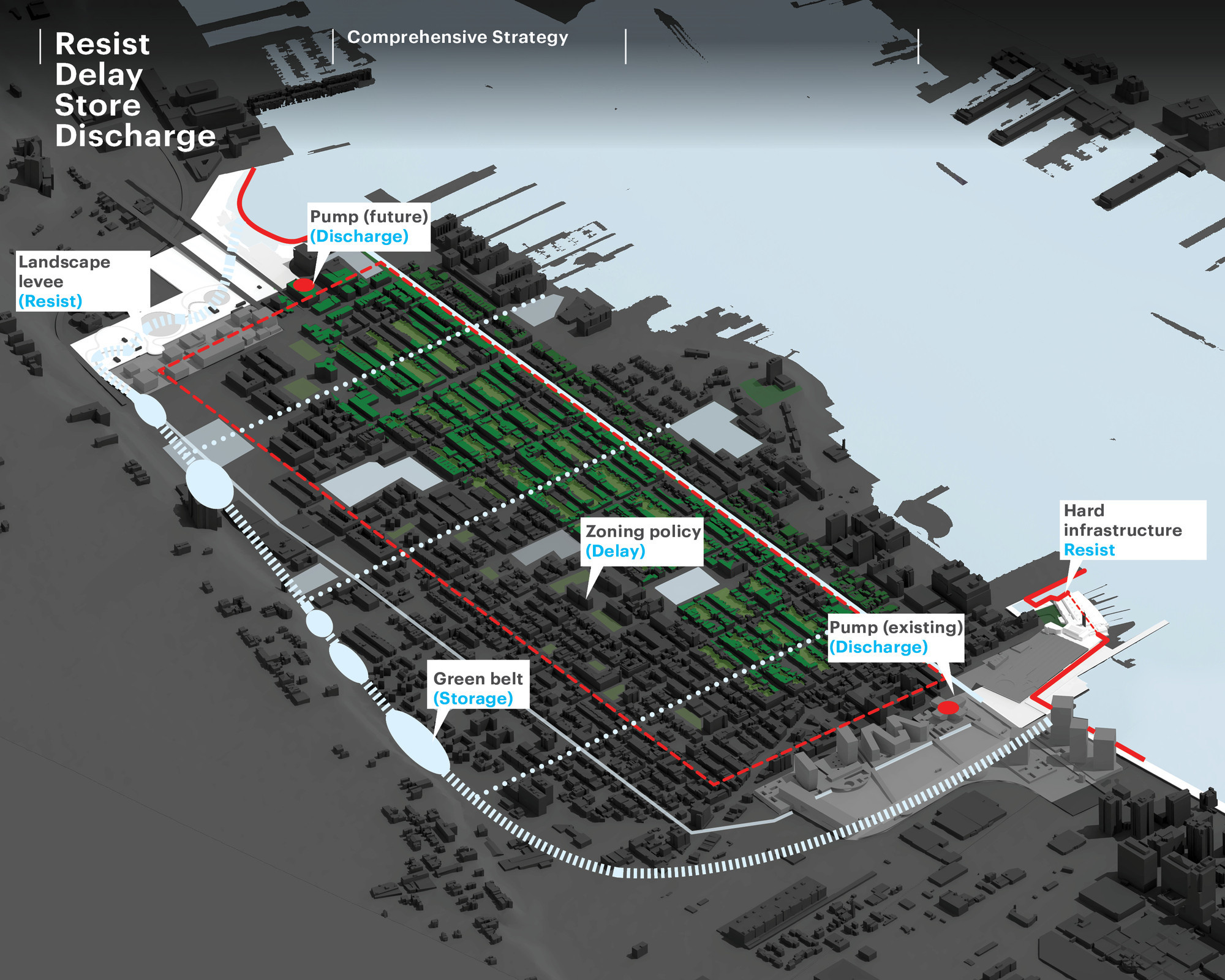

After Hurricane Sandy devastated the northeastern U.S. in 2012, Hoboken—a dense city perched on the edge of the Hudson River—suffered severe flooding. But instead of rebuilding defensively, Hoboken joined the Rebuild by Design initiative led by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development and supported by a multidisciplinary team including OMA, SCAPE, and Arcadis.

What They Did:

-

Created a “resist, delay, store, discharge” system to manage stormwater through green infrastructure and drainage tunnels.

-

Built new waterfront parks that also function as flood protection.

-

Prioritized equity by investing in vulnerable neighborhoods.

The results? Not only is the city more flood-resilient, but its public realm has been dramatically improved. Property values have risen, tourism has increased, and the city has become a model of integrated urban design.

“It’s about turning climate threats into an opportunity for transformation,” said Amy Chester, Managing Director of Rebuild by Design.

Hoboken, New Jersey, USA. Resist, Delay, Store, Discharge: a comprehensive strategy for Hoboken (Source: oma.com)

The proposed Hoboken Waterfront. (Source: oma.com)

Tactical Urbanism Meets Ecological Resilience

Not every solution needs to be a multi-million-dollar infrastructure project. Sometimes the path to long-term change starts small—with tactical interventions that are temporary, creative, and community-driven.

These include:

-

Pop-up wetlands or floating gardens to pilot green stormwater solutions.

-

Coastal art installations that raise awareness while protecting dunes.

-

Festival spaces that draw people to underused waterfronts, building new cultural relationships to water.

Example: In Rotterdam, the “Waterplein Benthemplein” is a public square that transforms into a temporary retention basin during heavy rain. On dry days, it’s a vibrant community sports and gathering space. This kind of multi-functional design makes resilience both visible and livable.

Inclusive Governance as a Catalyst

Unlocking co-benefits isn’t just about physical infrastructure—it’s about who makes decisions, and who benefits.

Cities that engage residents early and often in the design process are better able to:

-

Identify overlooked needs and opportunities.

-

Build trust and long-term stewardship.

-

Ensure that solutions serve everyone—not just wealthy or central districts.

“Design is not only what we build—it’s how we listen,” said Kate Orff, founder of SCAPE Landscape Architecture. “It’s how we shape equitable relationships between people and their environment.”

Economic Potential: Making the Business Case for Resilience

Adaptation strategies that yield co-benefits are often easier to fund and sustain because they appeal to a broader coalition—businesses, philanthropies, tourism boards, public health advocates.

Investing in resilient public space can:

-

Attract private development around improved amenities.

-

Increase property tax revenues.

-

Reduce long-term disaster recovery costs.

-

Spur entrepreneurial opportunities (waterfront cafes, cultural programming, ecological tourism).

According to the Global Commission on Adaptation, every $1 invested in climate resilience returns $4 in avoided losses and economic growth. This is not just a moral imperative—it’s a strategic investment.

Design as a Driver of Renewal

In summary, well-designed coastal adaptation projects don’t just defend—they redefine our relationship with water. They make cities more vibrant, inclusive, and future-ready. They turn the act of adaptation into an act of collective creativity and renewal.

|

Co-Benefit |

Example |

|

Tourism + Ecology |

Oyster reefs that support marine life and attract eco-tourists |

|

Jobs + Environment |

Wetland restoration employing local youth |

|

Health + Equity |

Shaded greenways that reduce heat and connect neighborhoods |

|

Culture + Climate Awareness |

Waterfront festivals celebrating water heritage and stewardship |

Conclusion: A Blueprint for Resilient Coastal Futures

Our coastlines are standing at a pivotal crossroads. Rising seas, stronger storms, and shifting climates have made one thing clear: we cannot afford to do nothing. Yet equally dangerous is the instinct to double down on the old playbook—more concrete, more barriers, more siloed thinking. The future won’t be won by building higher walls alone. It will be shaped by how well we learn to live with water—not against it.

What’s needed now is a fundamental shift in how we imagine, design, and govern coastal spaces. Coastal resilience is not just a technical challenge—it is a social, ecological, and cultural opportunity. It asks us to rethink what progress looks like, who gets a say in it, and how we measure success.

From Defence to Design with Purpose

Coastal adaptation must move beyond reactionary infrastructure. The places that will thrive in the face of climate change are those that:

-

Work with natural systems, not in opposition to them.

-

Design for flexibility, anticipating that coastlines will continue to evolve.

-

Centre people and place, respecting local identities, needs, and capacities.

Cities and communities are already showing us what’s possible. In New York, Living Breakwaters protect Staten Island while restoring marine habitats and educating local youth. In Cape Town, integrated water governance is helping to mitigate drought and flooding simultaneously. In Jakarta, where subsidence and sea level rise collide, plans for a green public waterfront seek to combine hard engineering with public space.

In Porthcawl, Wales, the redesign of the coastline wasn’t just about protection—it was about renewal. The community, faced with degrading sea defenses and rising risk, didn’t build a wall and walk away. They designed a multi-functional edge—part dune restoration, part flood protection, part promenade, all stitched together through civic engagement. The result? A safer, more vibrant, more cohesive town.

“Resilience isn’t just about holding the line—it’s about transforming vulnerability into vitality,” says Kristina Hill, Associate Professor at UC Berkeley, whose work bridges landscape architecture and urban planning.

A Living Framework for Action

There is no one-size-fits-all blueprint, but there is a set of guiding principles we must follow. The most successful coastal resilience strategies will be those that are:

Inclusive

Who builds resilience matters. Including Indigenous knowledge holders, youth, fisherfolk, local businesses, migrants, scientists, and artists ensures that solutions reflect real needs—not top-down assumptions. Lived experience is expertise.

Integrated

Nature doesn’t respect departmental boundaries. Neither should resilience. Cross-sector collaboration between urban planners, landscape architects, engineers, ecologists, and public health experts unlocks smarter, more holistic solutions.

Innovative

We must blend ecology, technology, and culture. Oyster reefs seeded with robotics. Floating parks. Sensor-equipped wetlands. Storytelling as climate infrastructure. Innovation means using all our tools—ancient and emerging—to imagine differently.

Iterative

Designing for the future means embracing uncertainty. Solutions should be adaptive, reversible, and regularly re-evaluated. Pilot projects, feedback loops, and flexible zoning allow for evolution as data, conditions, and communities change.

From Survival to Flourishing

In the coming decades, some coastlines will erode, some will be reshaped, and some may even be abandoned. But many can be reimagined—into places that absorb shock, support life, and invite joy.

Resilience isn’t about survival alone. It’s about creating coastlines where ecosystems thrive, economies grow, cultures endure, and communities feel safe and empowered.

We need to move from a mindset of scarcity and fear to one of possibility and design intelligence. With bold vision, inclusive leadership, and sustained investment, we can shape a new relationship between land, water, and people—one that doesn’t just hold back the tide, but rises with it.

“We can no longer treat climate risk as an environmental issue alone,” says Dr. Judy Curry, climate scientist and former chair of the School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences at Georgia Tech. “It is a profound infrastructure challenge—one that affects how we finance, build, and govern our cities.”

Featured Posts

Blog Topics

Urban environment & Public spaces

Stay updated with the latest articles and insights from The Landscape Lab. Here, you will find valuable information and engaging content.

Waterfront & Coastal Resilience

Stay updated with the latest articles and insights from The Landscape Lab. Here, you will find valuable information and engaging content.

Captivating Photography

Stay updated with the latest articles and insights from The Landscape Lab. Here, you will find valuable information and engaging content.

Why Read The Landscape Lab Blog?

The way we design and interact with landscapes is more important than ever. As cities expand, coastlines shift, and climate change reshapes our world, the choices we make about land, water, and urban spaces have lasting impacts. The Landscape Lab Blog is here to spark fresh conversations, challenge conventional thinking, and inspire new approaches to sustainable and resilient design.

If you’re a landscape architect, urban planner, environmentalist, or simply someone who cares about how our surroundings shape our lives, this blog offers insights that matter. We explore the intersections between nature and the built environment, diving into real-world examples of cities adapting to rising sea levels, innovative waterfront designs, and the revival of native ecosystems. We look at how landscapes can work with nature rather than against it, ensuring long-term sustainability and biodiversity.

By reading The Landscape Lab, you'll gain a deeper understanding of the evolving field of landscape design—from rewilding initiatives to regenerative urban planning. Whether it’s uncovering the forgotten history of resilient landscapes, analyzing groundbreaking projects, or discussing the future of green infrastructure, this blog provides a space for learning, inspiration, and meaningful dialogue.

Location:

The Landscape Lab

123 Greenway Drive

Garden City

NY 12345

United Kingdom

Contact Number:

Get in Touch:

contact@thelandscapelab.co.uk

© 2025 thelandscapelab.co.uk - Your go-to blog for landscaping insights