Architecture Rooted in Culture, Climate, and Community

Mariam Kamara does not design buildings for spectacle; she designs spaces that honor the way people truly live. The Nigerien architect, founder of the practice Atelier Masōmī, believes that architecture should be deeply connected to cultural identity, climate, and history, particularly in parts of the world where the built environment has long been shaped by colonial and Western influences. For Kamara, modernity is not defined by European forms, nor is architecture an exclusive domain for Western designers to dictate. Instead, she argues that the so-called canon of great buildings largely ignores the built world of Africa, Asia, and Latin America—places where architecture is, and has always been, an expression of local materiality, craftsmanship, and environmental intelligence.

Compressed earth block production - Niamey 2000 (Source: united4design_Torsten Seidel_archdaily.com)

Kamara’s approach to architecture is not about erasing tradition but reinterpreting it for contemporary needs. She designs with a clear mission: to create spaces that are culturally and climatically appropriate, using local materials, passive techniques, and community-driven solutions. "You cannot hide a bad space when you don’t have access to shiny things," she says. "It becomes more about what the space is doing and how it is bringing people together." This philosophy underpins her work, where design is not a luxury, but a tool for dignity, functionality, and human connection.

Building for People: Context Over Aesthetics

At the core of Kamara’s practice is the belief that architecture should elevate lived experiences. She does not chase sleek, glass-covered designs that could exist anywhere; instead, she asks: How do people live here? What do they need? What materials make sense? How can buildings respond to the local climate instead of fighting against it?

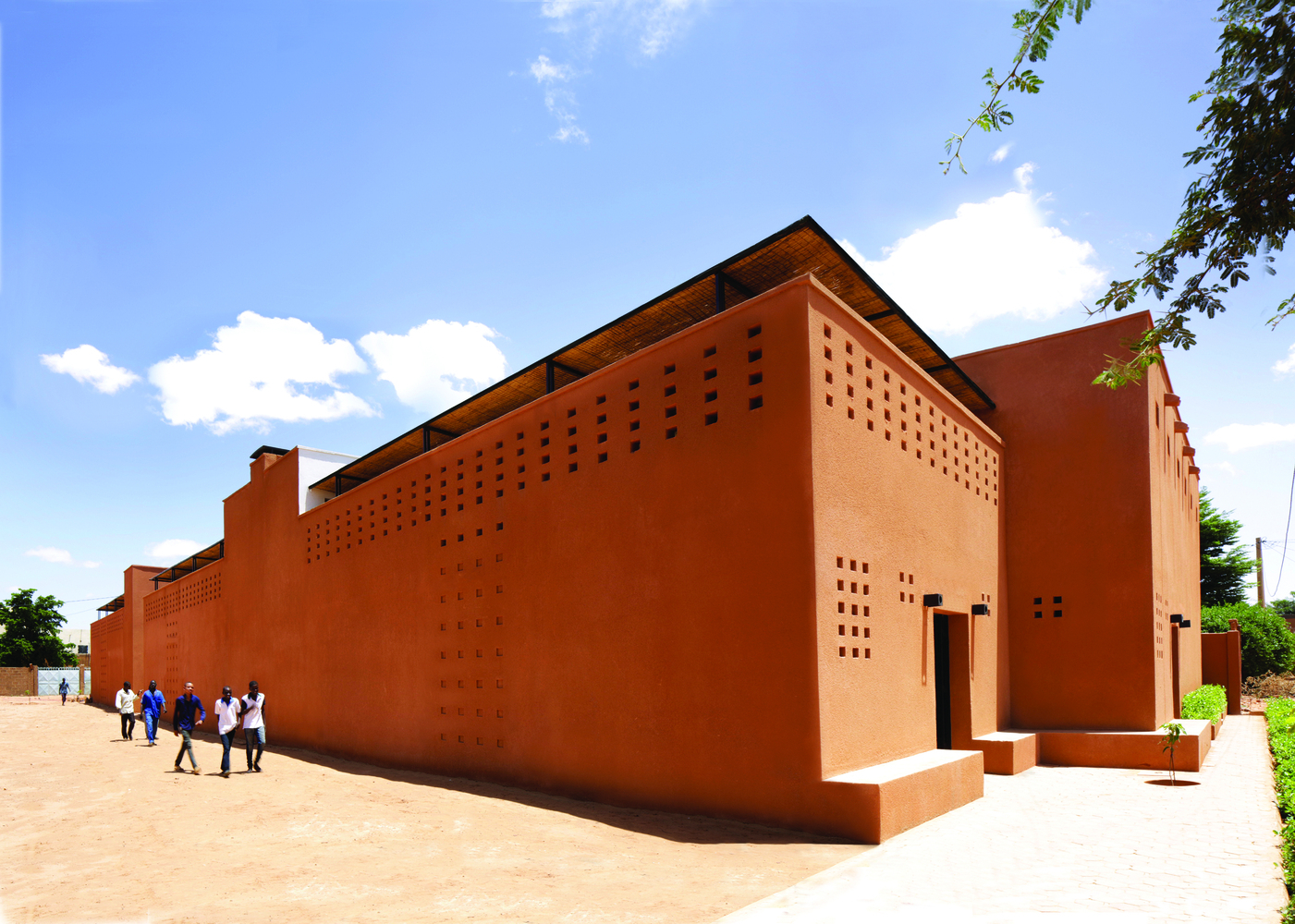

One of her most defining projects is the Niamey 2000 Housing development in Niger’s capital. This project challenges the Western-style concrete housing that dominates urban expansion in Africa. Instead of using imported materials that trap heat and deteriorate quickly, Kamara reintroduced traditional adobe construction—thick earthen walls that naturally regulate temperature, reducing the need for air conditioning. The project incorporates courtyards and shaded outdoor spaces, reflecting the social and environmental logic of traditional Sahelian architecture. The result? Homes that are not only sustainable but deeply rooted in the culture and everyday rhythms of the people who live in them.

Niamey 2000 Housing - Niamey, Niger (Source: Torsten Siedel_united4design_archdaily.com)

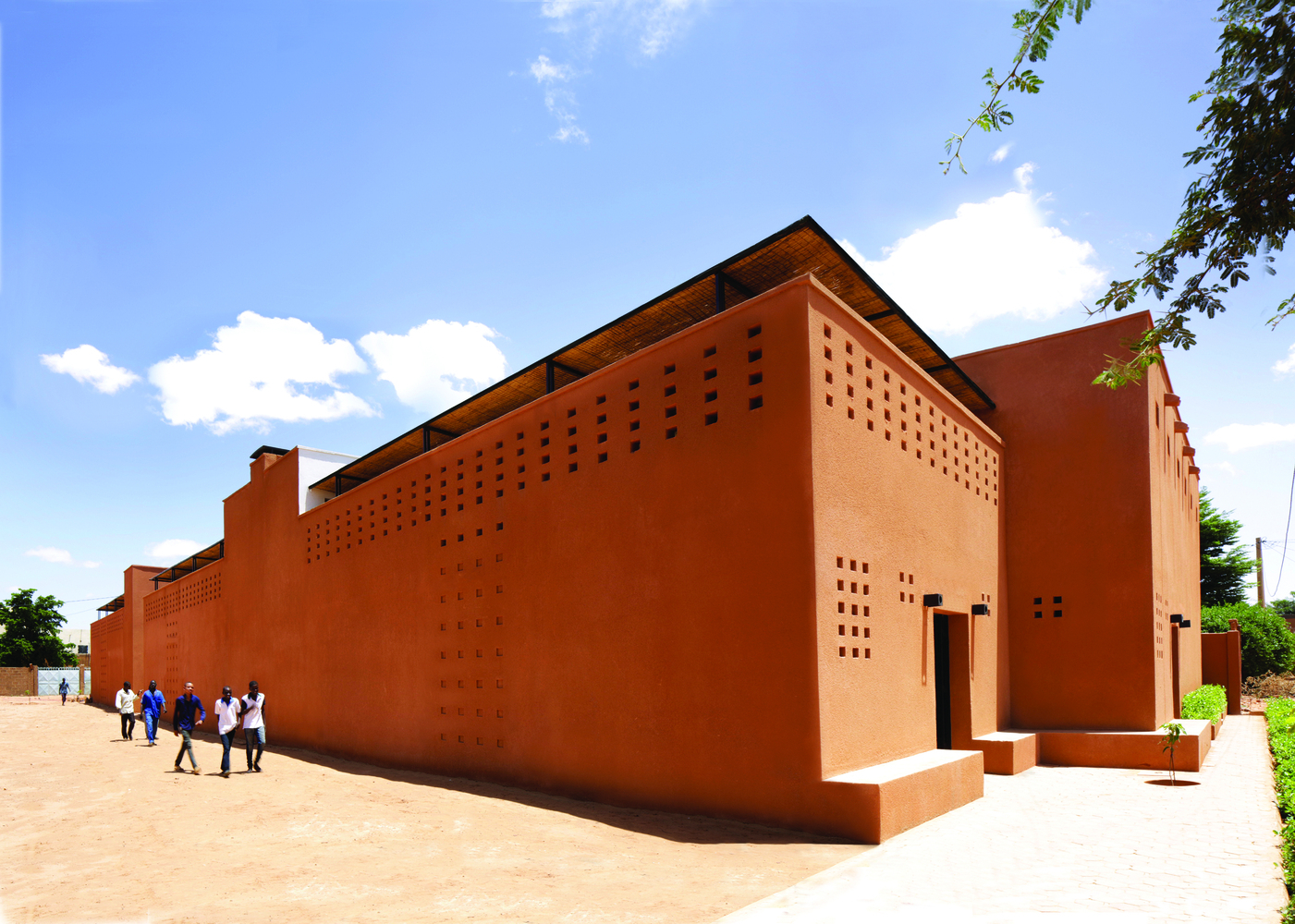

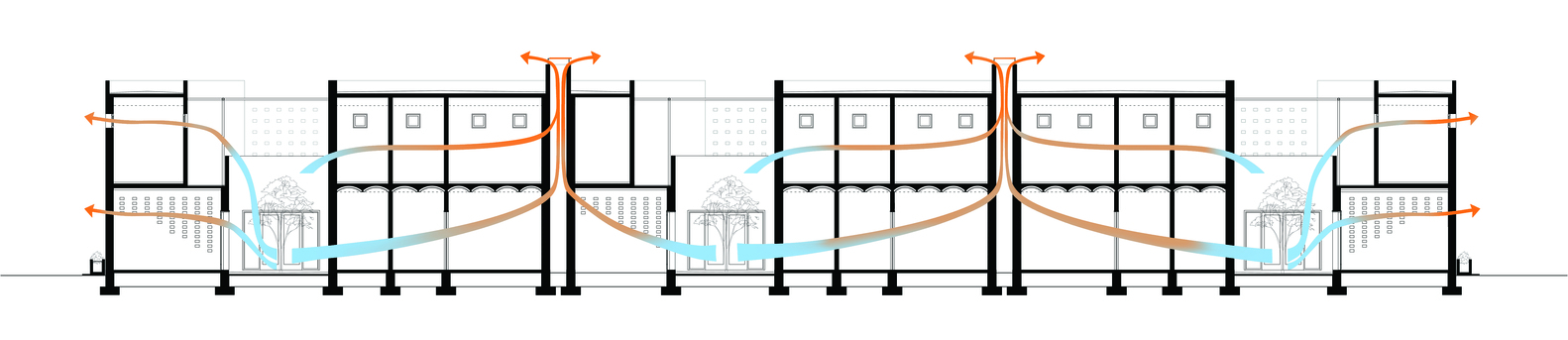

Similarly, Kamara's work on the Hikma Religious and Secular Complex in Dandaji, Niger, showcases her ability to blend history with modern function. A former mosque was transformed into a library and community center, while a new mosque was built using compressed earth bricks. The structure respects the vernacular architecture of the region while providing a contemporary gathering space for knowledge, worship, and communal activities.

By using locally available materials and passive cooling techniques, the project reduces energy consumption while embracing the wisdom of traditional desert architecture.

Hikma Religious and Secular Complex in Dandaji, Niger (Source: James Wang_atelier masōmī)

Hikma Religious and Secular Complex in Dandaji, Niger (Source: James Wang_atelier masōmī)

Kamara sees architecture as a force to empower communities. This is evident in her work with women’s cooperative projects, where she designs structures that not only serve functional purposes but also become catalysts for economic and social independence.

A New Vision for African Modernity

Kamara’s work is a direct critique of the dominant architectural narratives that have historically dismissed African, Middle Eastern, and Indigenous design traditions in favor of European ideals. She argues that modernity is not a singular aesthetic but a mindset—one that can be deeply embedded in regional identity.

Her project for the Martha Thorne Fellowship, in collaboration with David Adjaye and the Rolex Mentor and Protégé Arts Initiative, embodies this vision. She explored how vernacular design strategies can inform the future of African cities, particularly in rapidly urbanizing areas. By integrating local materials like laterite stone, earth, and timber, her designs prove that African architecture does not need to mimic Western skylines to be considered modern or progressive.

Kamara is particularly vocal about challenging the influence of colonial urban planning, which has led to disconnected, unsustainable cities across Africa. Instead of rigid grids and car-centric layouts, she envisions cities where public spaces, courtyards, and shaded walkways encourage community interactions—where the built environment enhances, rather than disrupts, the social fabric.

Atelier Masōmī’s Dandaji Regional Market (Source: Maurice Ascani)

Materials, Climate, and Sustainability

A key pillar of Kamara’s work is the use of low-cost, renewable, and locally sourced materials. Instead of relying on imported concrete and glass, she champions techniques that have existed for centuries in Niger and the Sahel region.

Some of her sustainable design strategies include:

-

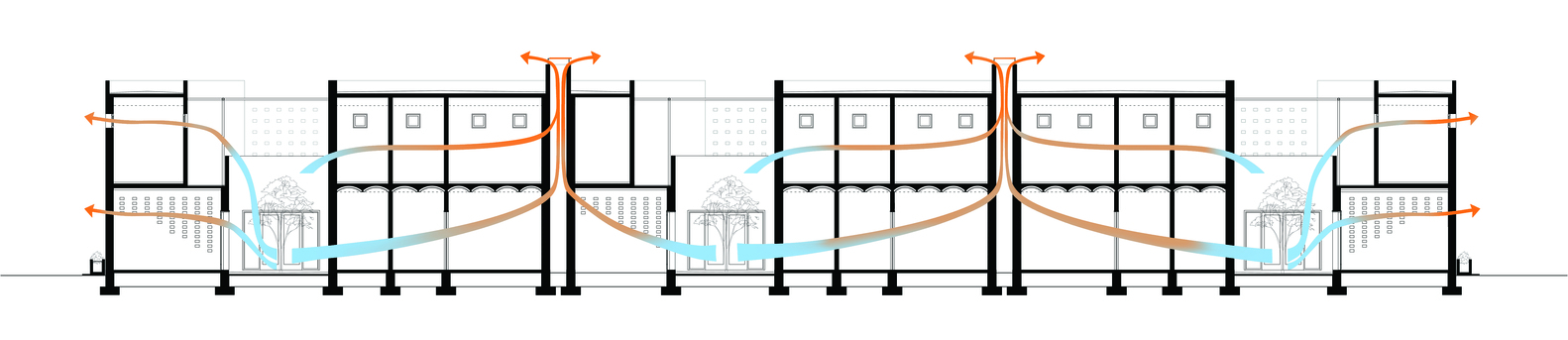

Passive Cooling: Thick earthen walls, cross-ventilation, and shaded courtyards reduce the need for artificial cooling.

-

Adobe and Compressed Earth Blocks: These materials offer thermal mass, keeping interiors cool in the scorching heat of Niger’s climate.

-

Minimal Water Usage: Many of her projects incorporate water-efficient landscaping with native plants suited to dry conditions.

(Source: Mariama Kah_archdaily.com)

Hikma Religious and Secular Complex in Dandaji, Niger (Source: James Wang_atelier masōmī)

Ventilation System - Niamey 2000 (Source: united4design.com)

One of the most exciting aspects of Kamara’s work is her ability to reimagine traditional architectural forms for contemporary needs. In her public buildings, she often references Sudano-Sahelian architecture, known for its sculptural mud-brick facades and deep-set openings that provide natural shade. Rather than viewing these traditions as outdated, she sees them as practical, tested solutions that can inform a more sustainable future.

Daring to Dream: Architecture as a Social Catalyst

For Kamara, architecture is more than form and function—it is about dreaming and daring to create spaces that uplift people. She believes in designing with purpose: “to elevate lived experience,” and “to dare to do something that would make someone dream.”

Her work challenges the aesthetic dominance of Western modernism, pushing for an architectural future where African, Middle Eastern, and Indigenous voices define their own built environments. Through projects that prioritize human experience, cultural continuity, and environmental harmony, she is reshaping what modern architecture can—and should—be.

As cities across the Global South continue to grow, Kamara’s work provides a roadmap for how architecture can be sensitive to local traditions yet forward-thinking, sustainable yet ambitious, deeply rooted yet daring to dream.

Her buildings are not just structures; they are narratives—stories of the past, reflections of the present, and visions for the future. Through them, Mariam Kamara is proving that great architecture is not about imported aesthetics but about creating places that truly belong to the people who inhabit them.

Atelier Masōmī’s Dandaji Regional Market (Source: Maurice Ascani)

Artisan Valley - Niamey, Niger (Source: mariamissoufou.com)

Conclusion: Reclaiming Architecture for People and Place

Mariam Kamara’s designs tell a different story—one where architecture is not an imposition but a response; not an isolated object, but an integral part of the social and environmental fabric. She envisions buildings not as static entities, but as living, breathing spaces that serve and evolve with the people who inhabit them.

By embracing local materials, passive climate strategies, and vernacular techniques, Kamara redefines what it means to create sustainable, dignified, and functional spaces in the developing world.

Beyond the buildings themselves, her work has profound social implications. By prioritizing civic spaces, educational institutions, and housing that uplifts communities, Kamara’s architecture is a catalyst for change. Her projects—whether the Hikma Religious and Secular Complex, the Niamey Cultural Center, or her housing prototypes—are more than just structures; they are acts of empowerment, reclamation, and reimagination.

Her philosophy is one of humility and purpose. In a world where architectural prestige is often measured by spectacle, Kamara’s work proves that true innovation lies in thoughtfulness, relevance, and sensitivity. She dares to ask: Whose needs are we designing for? What histories and traditions must we honor? How can architecture serve not just the elite, but everyday people?

As climate change and urbanization reshape our landscapes, Kamara’s approach offers a blueprint for the future—one where sustainability is not just about reducing carbon footprints but about building in a way that respects the past, serves the present, and anticipates the future. Her work is a testament to the idea that architecture, at its best, is not an abstract art—it is a deeply human endeavor.

By elevating lived experiences, embracing local intelligence, and designing spaces that inspire and endure, Mariam Kamara is not just redefining architecture—she is reclaiming it for the people who need it most.