Landscape and Urbanism Theory: A Multidisciplinary Approach to Contemporary Cities

Introduction

The design and development of cities, landscapes, and territories have always been influenced by broader theoretical frameworks. Landscape and Urbanism Theory serves as a crucial foundation for understanding the social, ecological, political, and spatial interrelations that shape contemporary urban environments. By drawing upon diverse disciplines such as art, ecology, geography, sociology, anthropology, and architecture, this field seeks to develop critical approaches that guide the practice of landscape architecture and landscape urbanism.

In this article, we will explore historical and contemporary theories that have informed urban and landscape design, emphasizing their relevance to Advanced Urban Design and Advanced Landscape Design projects. We will also discuss how critical theory can be applied in design practice and writing, reinforcing the role of landscape and urbanism theory in creating sustainable, inclusive, and resilient environments.

Historical Foundations of Landscape and Urbanism Theory

1. The Picturesque and the Early Theories of Landscape

Historically, landscape architecture was deeply rooted in the aesthetic traditions of the picturesque, sublime, and beautiful, particularly in the 18th and 19th centuries. Influenced by artists such as Claude Lorrain and William Gilpin, early landscape architects like Lancelot “Capability” Brown and Frederick Law Olmsted sought to design landscapes that were visually harmonious and functionally integrated with natural systems.

Olmsted’s work on Central Park in New York (1857) marked a shift in landscape design by emphasizing public health, social cohesion, and ecological balance. This perspective laid the groundwork for modern landscape urbanism, which integrates environmental and social considerations in city planning.

Lancelot “Capability” Brown (Source:graduatelandscapes.co.uk)

2. Modernist Urbanism: Functionalism and the Machine Aesthetic

The early 20th century saw the rise of Modernist urbanism, heavily influenced by the Bauhaus movement and architects like Le Corbusier. His vision of the “Radiant City” (La Ville Radieuse) proposed strict zoning and high-rise structures to optimize functionality and efficiency. This approach led to the urban renewal projects of the mid-20th century, which prioritized large-scale infrastructural interventions but often neglected social and ecological factors.

Meanwhile, urban theorists such as Lewis Mumford and Jane Jacobs challenged the rigidity of modernist planning. Jacobs, in particular, advocated for human-scale urbanism, emphasizing the importance of public spaces, mixed-use neighborhoods, and community participation. Her seminal work, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961), continues to influence contemporary urbanism.

La Ville Radieuse (Radiant City) - Le Corbusier (Source:Pinterest)

3. Postmodern and Ecological Urbanism

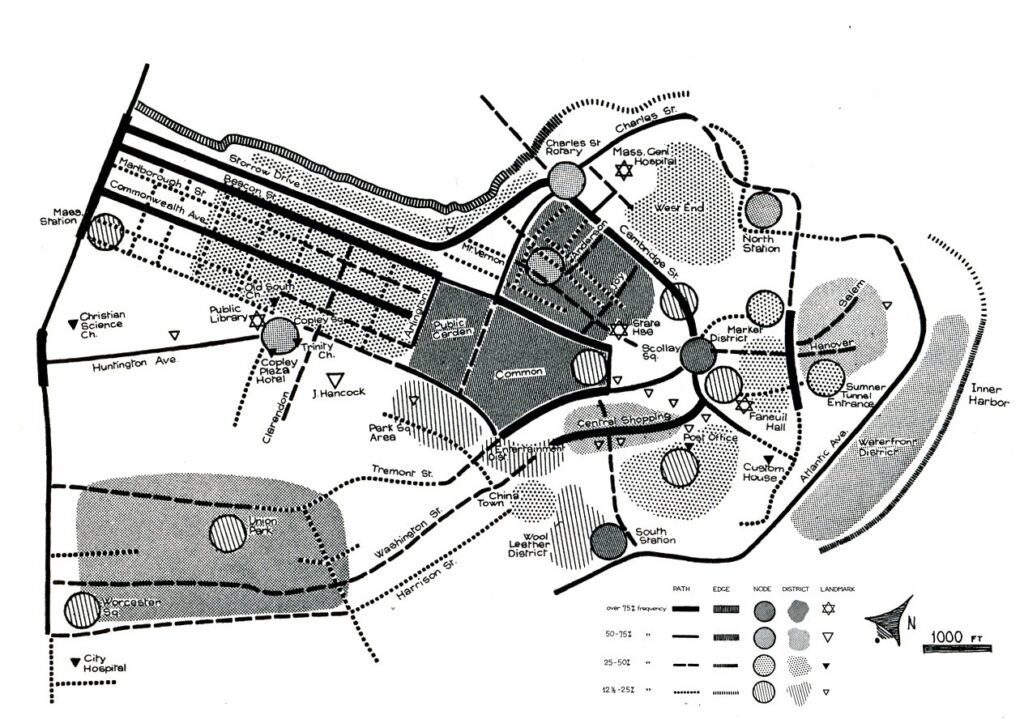

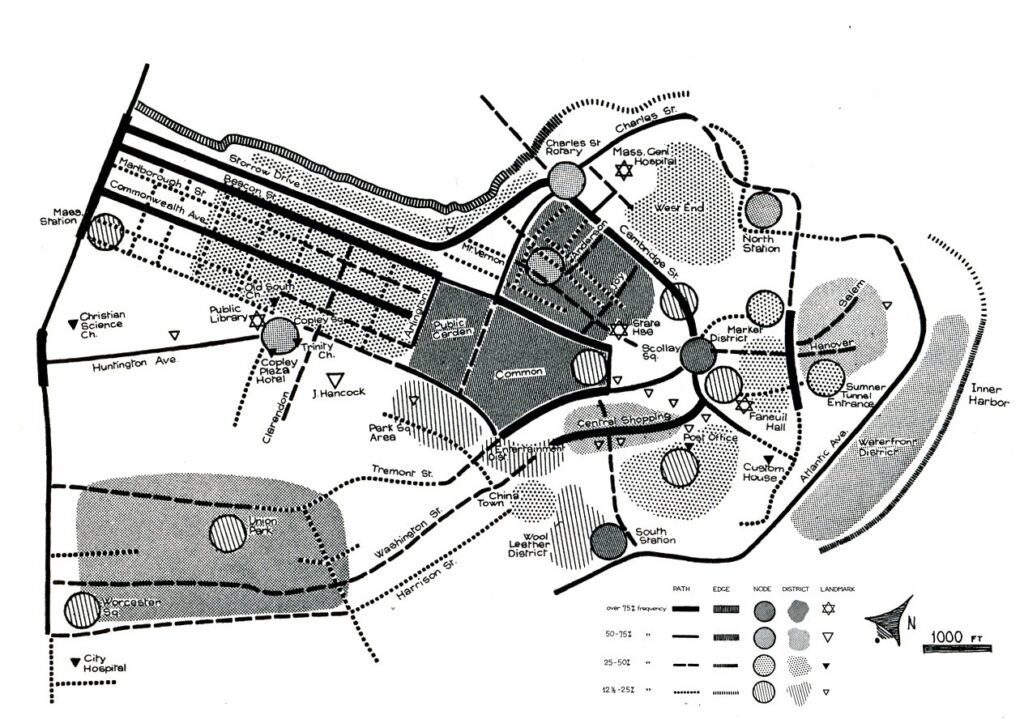

In reaction to modernist planning, postmodern urbanism emerged in the late 20th century, promoting context-sensitive, diverse, and historic-conscious design approaches. Figures like Kevin Lynch introduced the concept of legibility in urban landscapes, arguing that cities should be designed with recognizable paths, edges, districts, nodes, and landmarks to improve navigation and experience.

Simultaneously, Ian McHarg pioneered ecological urbanism with his book Design with Nature (1969), advocating for a systems-based approach to urban planning that integrates natural processes, hydrology, and biodiversity. His theories directly influenced green infrastructure, urban resilience planning, and contemporary landscape urbanism.

Kevin Lynch - The Image of the City (Source:urbandesignlab.in)

Contemporary Theories in Landscape and Urbanism

1. Landscape Urbanism: A Shift Toward Process-Oriented Design

Coined by Charles Waldheim in the early 2000s, landscape urbanism challenges traditional urban planning by positioning landscape as the primary organizing element of the city. Rather than relying on rigid zoning and master planning, landscape urbanism promotes adaptive, process-based design that accommodates ecological and social change.

Projects like New York’s High Line (designed by James Corner Field Operations) exemplify this approach, transforming abandoned infrastructure into dynamic public space through ecological succession, social programming, and adaptive reuse.

High Line - NYC - (Source: Elizabeth Villalta_Unsplash)

2. The Social and Political Dimensions of Urbanism

Theories of social urbanism and right to the city (Henri Lefebvre, 1968) emphasize that urban design must serve the needs of diverse populations rather than prioritizing economic or aesthetic concerns. This perspective is particularly relevant in discussions of gentrification, informal settlements, and participatory design processes.

Contemporary urbanists like Raquel Rolnik and David Harvey critique neoliberal urban development, arguing that privatization and commercialization of public spaces undermine social equity. Cities like Medellín, Colombia, have implemented social urbanism strategies, using public transportation, cultural spaces, and inclusive planning to uplift marginalized communities.

Right to the City - Henri Lefebvre (Source: parcitypatory.org)

3. Resilient and Regenerative Urbanism

Climate change and environmental degradation have prompted a shift toward resilient and regenerative urbanism, focusing on flood mitigation, carbon sequestration, biodiversity conservation, and circular economies.

Urban projects such as Copenhagen’s climate-adaptive parks, Singapore’s “City in a Garden” vision, and Rotterdam’s water plazas integrate ecological processes with urban infrastructure to create climate-responsive cities.

Application of Theory in Design and Writing

1. Integrating Theory into Advanced Urban and Landscape Design

Understanding landscape and urbanism theory is crucial for designers working on Advanced Urban Design and Advanced Landscape Design projects. By drawing on principles from ecology, sociology, and political theory, designers can create resilient, inclusive, and adaptive spaces that respond to contemporary challenges.

For example:

Ecological urbanism informs the design of sustainable green corridors and stormwater management systems.

Social urbanism encourages community participation in the planning of public spaces.

Political ecology examines how power structures influence access to green spaces and urban resources.

2. Writing as a Tool for Critical Reflection

The application of theory extends beyond design into writing and research, allowing practitioners to critically reflect on their work and contribute to academic discourse. Writing in both reflective and propositional modes helps articulate design intentions, justify decisions, and propose innovative solutions.

For instance, an urban designer working on a post-industrial waterfront regeneration project might use landscape urbanism principles to argue for a hybrid landscape-infrastructure solution that integrates public space with ecological restoration.

Conclusion: Strengthening Landscape and Urbanism Theory

Landscape and urbanism theory is not static—it evolves in response to shifting cultural, environmental, and technological contexts. By interrogating established and emerging concepts, designers can craft urban environments that are socially just, ecologically resilient, and spatially innovative.

As cities face complex challenges like climate change, social inequality, and rapid urbanization, the integration of art, ecology, geography, sociology, anthropology, and architecture becomes essential. By drawing on interdisciplinary knowledge, urban and landscape designers can shape the future of cities in ways that prioritize human experience, ecological balance, and spatial justice.

Through both design practice and critical writing, we strengthen the theoretical foundations of landscape urbanism—ensuring that cities and landscapes are not just functional, but meaningful places that enhance life, culture, and the environment.