Introduction

Jane Jacobs, a self-taught urbanist and activist, transformed the way we think about cities. Her book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961), was a direct critique of mid-20th-century urban planning, particularly the large-scale redevelopment projects that prioritized automobiles over people. She argued for human-scale urbanism, which emphasizes the importance of public spaces, mixed-use neighborhoods, and community participation in shaping vibrant cities.

Her ideas were revolutionary at the time, challenging the dominant vision of modernist urbanism promoted by planners like Le Corbusier and Robert Moses, who favored high-rise developments and rigid zoning. Instead, Jacobs championed the organic, diverse, and lively qualities of traditional city neighborhoods. More than 60 years later, her theories remain a cornerstone of contemporary urban planning, influencing movements such as New Urbanism, Tactical Urbanism, and Smart Growth.

Jane Jacobs’ Vision for Cities

1. Mixed-Use Neighborhoods: The Power of Diversity

Jacobs believed that the best neighborhoods are those that accommodate a variety of uses—residential, commercial, and recreational—within the same area. She saw zoning segregation (where housing, retail, and offices were separated) as a key factor in creating dull and lifeless cities.

Example from Jacobs’ Time: Greenwich Village, New York City – A lively neighborhood with a mix of shops, homes, cafes, and offices, all within walking distance. This diversity allowed for natural social interactions and economic vitality.

Modern Example: The Meatpacking District, NYC, has transformed from an industrial hub to a thriving mixed-use neighborhood with residential buildings, boutique hotels, restaurants, and offices. Its success reflects Jacobs’ principle that functional diversity enhances urban life.

The Meatpacking District - NYC (Source: mas.org)

2. Walkability and Human-Scale Design

Jacobs argued that cities should prioritize pedestrians over cars, fostering a sense of community and interaction. She was deeply opposed to highways cutting through neighborhoods, as seen in her fight against Robert Moses' proposed expressway through Lower Manhattan.

Example from Jacobs’ Time: Boston’s West End was demolished for highways and modernist housing projects, leading to social fragmentation and economic decline.

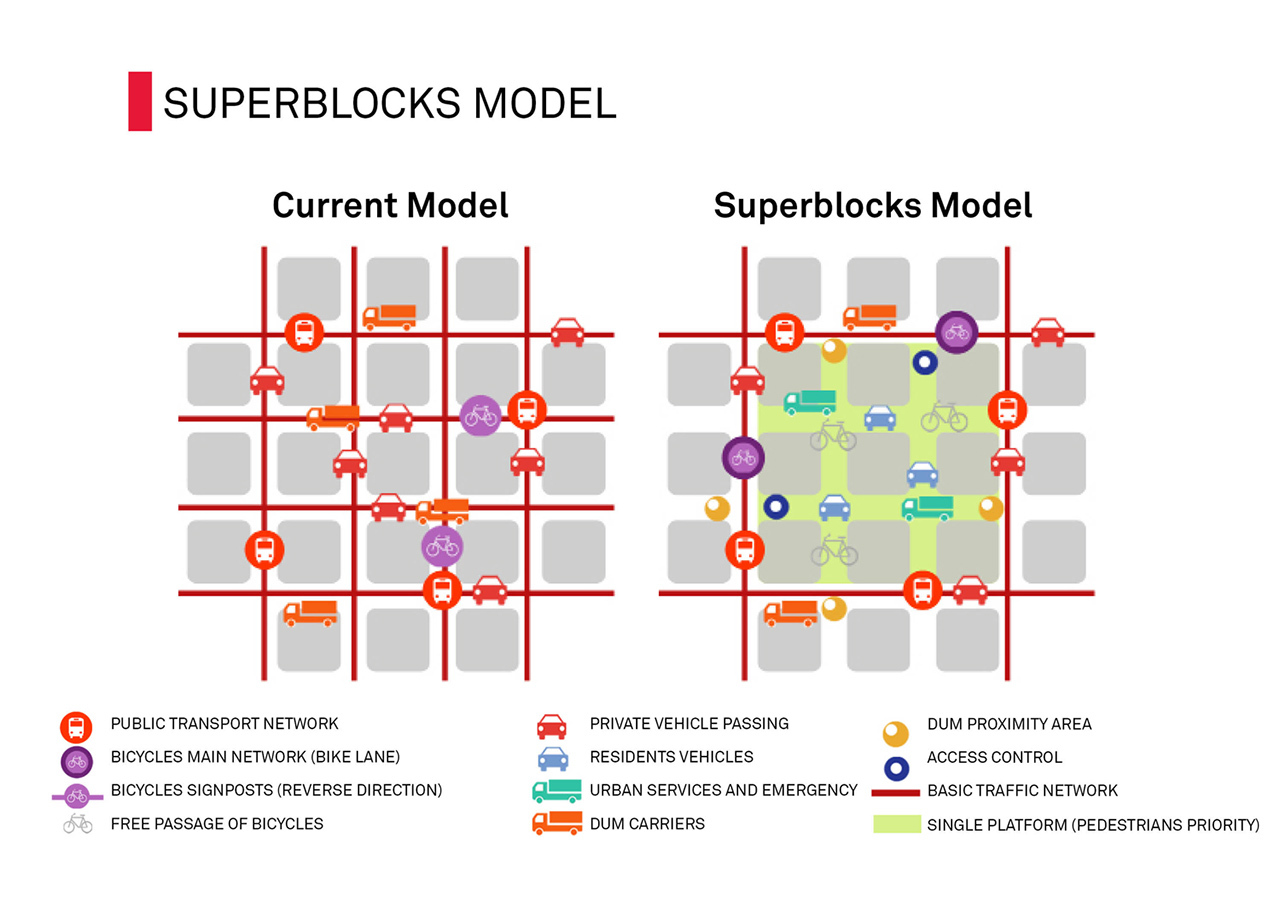

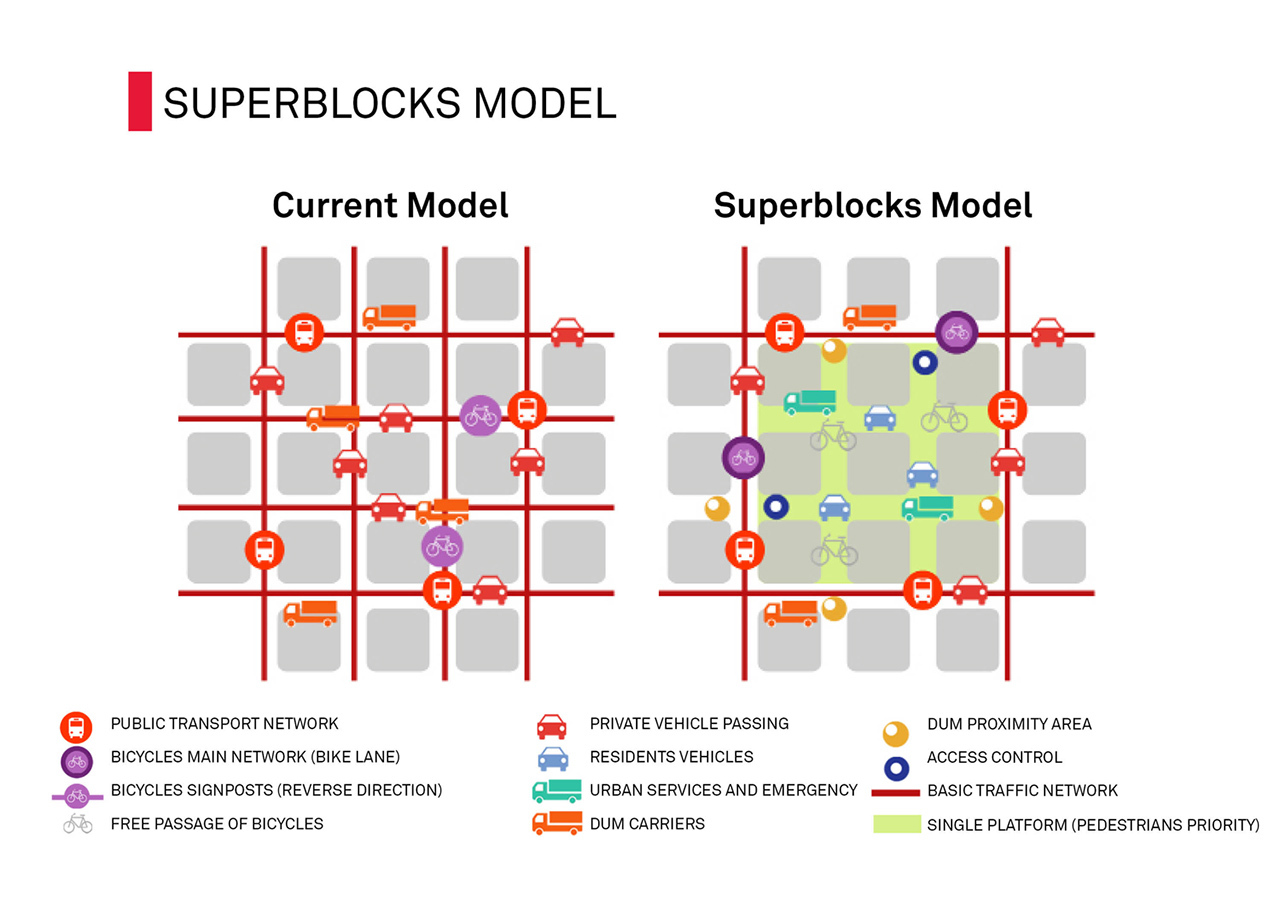

Modern Example: Barcelona’s Superblocks – A contemporary effort to prioritize pedestrians by restricting traffic in certain zones, creating vibrant public spaces, reducing pollution, and enhancing community life.

Superblocks - Barcelona (Source: barcelonarchitecturewalks.com)

Superblocks - Barcelona (Source: citiespeoplelove.co)

3. "Eyes on the Street": Safety Through Social Interaction

One of Jacobs’ most famous concepts is "eyes on the street", which suggests that the safest neighborhoods are those where people naturally observe public spaces, deterring crime. She opposed the idea of isolated public housing projects, which lacked this informal surveillance.

Example from Jacobs’ Time: Public housing projects in cities like Chicago and St. Louis (e.g., Pruitt-Igoe) were designed with large, vacant open spaces that felt unsafe due to a lack of street-level activity.

Modern Example: Copenhagen’s Strøget – One of the world’s longest pedestrian streets, where shops, cafes, and public seating create constant street activity, enhancing both security and sociability.

Strøget - Copenhagen (Source: Svend Nielsen_Unsplash)

4. Public Spaces as Social Hubs

Jacobs argued that great cities are built around high-quality public spaces—parks, plazas, and street corners—where people naturally gather. She believed that small, well-used parks were better than large, underutilized ones.

Example from Jacobs’ Time: Washington Square Park, NYC – A dynamic urban space that remains a model of community interaction.

Modern Example: The High Line, NYC – This elevated park transformed an abandoned railway into a green public space, attracting millions of visitors and integrating Jacobs' idea that public spaces should serve multiple functions.

High Line - NYC (Source: Simon Bak_Unsplash)

5. Community Participation and Bottom-Up Planning

Jacobs strongly believed that urban planning should be community-driven, rather than dictated by distant bureaucrats. She emphasized that residents know their neighborhoods best and should have a voice in development decisions.

Example from Jacobs’ Time: Her activism in Greenwich Village successfully stopped the Lower Manhattan Expressway, which would have destroyed historic neighborhoods.

Modern Example: The Medellín Metrocable (Colombia) – A project that integrated community participation in urban mobility, connecting informal settlements in the hills to the city center, improving accessibility, and enhancing social inclusion.

The Metrocable - Medellin (Source: gondolaproject.com)

Jacobs’ Influence on Contemporary Urbanism

1. The Rise of New Urbanism

Jacobs’ principles are central to the New Urbanism movement, which promotes walkability, mixed-use neighborhoods, and human-scale design. Cities worldwide have embraced her ideas in projects that prioritize livability over car-centric planning.

Example: Seaside, Florida – A New Urbanist community designed with Jacobs’ principles in mind, featuring walkable streets, mixed-use zoning, and a vibrant public realm.

2. Tactical Urbanism and DIY Urbanism

Inspired by Jacobs’ bottom-up approach, many modern urban interventions begin at the grassroots level, using temporary, low-cost strategies to improve public spaces.

Example: Pavement to Parks (San Francisco) – Transforming excess road space into mini-parks and plazas, encouraging community interaction.

Pavement to Parks - San Francisco (Source: globaldesigningcities.org)

3. Smart Growth and Sustainable Urbanism

Jacobs’ advocacy for dense, mixed-use development has influenced policies in sustainable urban planning. Many cities now prioritize infill development (revitalizing existing urban areas) over suburban sprawl.

Example: Portland, Oregon – A city that embraces compact development, public transportation, and pedestrian-friendly design, all key aspects of Jacobs' vision.

4. Placemaking and Public Space Revitalization

Jacobs’ emphasis on public spaces has shaped the placemaking movement, which focuses on creating lively, people-friendly environments.

Example: Times Square, NYC – Previously dominated by traffic, it has been reclaimed as a pedestrian plaza, aligning with Jacobs’ belief in the importance of vibrant public spaces.

Conclusion: Jane Jacobs’ Enduring Legacy

Jane Jacobs’ vision of human-scale urbanism has reshaped urban planning worldwide. Her advocacy for walkability, mixed-use development, public spaces, and community participation continues to influence how cities are designed and experienced today. From Barcelona’s Superblocks to New York’s High Line, contemporary urbanism is deeply rooted in her ideas.

As cities face challenges like climate change, rapid urbanization, and social inequality, Jacobs’ principles remain more relevant than ever. By prioritizing people over cars, neighborhoods over megaprojects, and local voices over top-down planning, we can create thriving, inclusive, and resilient cities for future generations—just as she envisioned.