Introduction: When Streets Turn into Rivers

Across many cities, the same picture keeps repeating: a cloudburst, gutters overwhelmed, streets turned into rivers, basements and subways flooding within minutes. At the same time, summers are getting hotter and drier, water quality regulations are tightening, and communities are asking for greener, healthier public spaces.

Into this complex brief step landscape architects.

Over the last two decades, they have begun to treat public space not just as surface décor laid over an engineering system, but as infrastructure in its own right. Bioretention basins, water squares, sponge parks and bioswales are four of the most powerful tools in this new vocabulary. They together form the physical grammar of the “sponge city”: urban landscapes that absorb, store, clean and slowly release water rather than pushing it into pipes as fast as possible.

This article explores what each of these typologies is, how they work, why and when landscape architects choose them, and what we can learn from leading practices that have delivered built projects on the ground.

The Rise of the Sponge City: Landscape as Infrastructure

The drivers are clear. Many cities face more intense rainfall events, aging “grey” sewers, and regulatory pressure to reduce combined sewer overflows and pollutants entering rivers and coasts (Gross, 2009; Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, 2013). In parallel, planners and citizens want more trees, more shade, more access to water and more visible climate action in daily life (Zhang, 2023; Natural England, 2009).

Green stormwater infrastructure (GSI) – and within it, bioretention basins, bioswales, water squares and sponge parks – has emerged as a way to reconcile these agendas. Research on bioretention and green streets shows that properly designed vegetated systems can significantly reduce runoff volumes and peaks, lower pollutant loads and create habitat, often at competitive life-cycle cost compared to conventional drainage (IWA, 2022; Bjørn et al., 2023; Im et al., 2019).

Landscape architects have been central to this shift because they operate at the intersection of:

-

Hydrology – understanding how water moves through a catchment and a site.

-

Form and experience – shaping spaces that people want to inhabit.

-

Governance and narrative – articulating a story that can bring transport departments, utilities, water boards and communities into the same project.

The four typologies below show how that plays out in practice.

Bioretention Basins: The Workhorse that Disappeared in Plain Sight

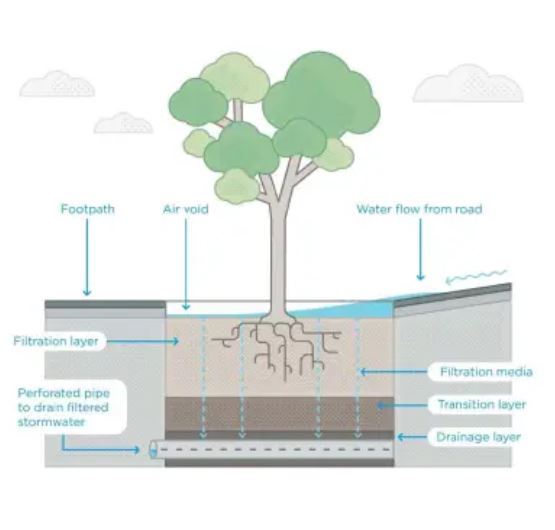

If there is a single unsung hero of the sponge city, it is the bioretention basin. Often labelled “rain garden” in public communication, a bioretention basin is a shallow planted depression with engineered soil, designed to temporarily store runoff from roofs, pavements or streets, then allow it to infiltrate or pass through underdrains. Pollutants are removed by sedimentation, filtration, plant uptake and microbial processes (EPA, n.d.; Gross, 2009).

In plan, they can read as ordinary planting beds. In section, they are highly tuned hydrological devices.

A good example is Orange Mall Green Infrastructure at Arizona State University, designed by Colwell Shelor Landscape Architecture. What was once a campus road has become a pedestrian promenade structured around a series of bioretention basins that intercept runoff from the surrounding hardscape. The basins help manage flood risk during extreme events in a desert climate while also delivering shade, social space and a strong landscape identity (Landscape Architecture Foundation, 2015).

Before (Source: landscapeperformance.org/case-study-briefs/ASU-orange-mall)

After (Source: colwellshelor.com/mies_portfolio/asu-orange-mall-student-pavilion/)

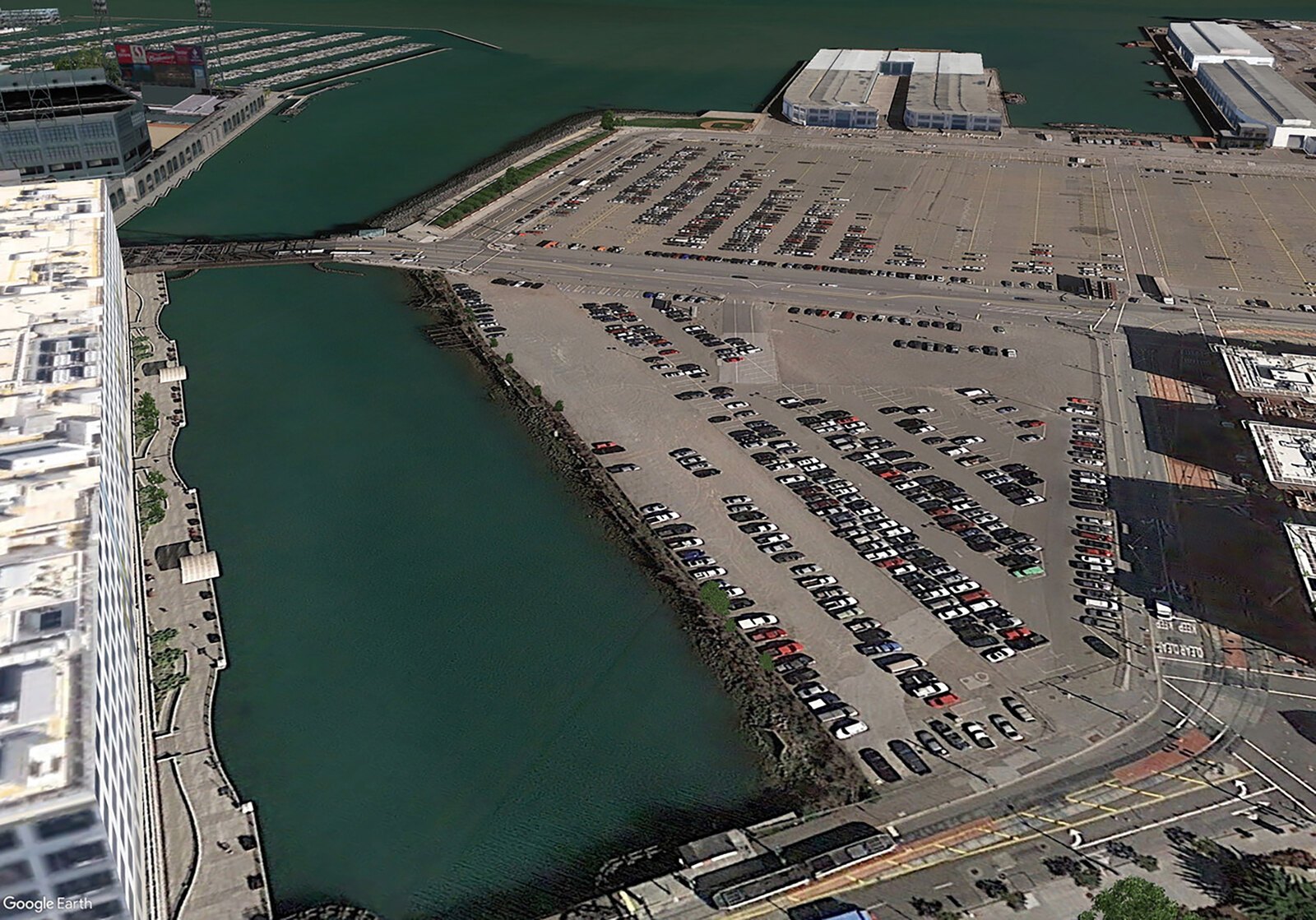

Similarly, Mission Creek Stormwater Park in San Francisco, by CMG Landscape Architecture, uses chains of bioretention planters along a waterfront promenade to treat runoff from adjacent streets before it reaches the creek. The “infrastructure” is experienced as a series of lush gardens and seating niches.

Before (Source: landscapeperformance.org/case-study-briefs/mission-creek)

After (Source: landscapeperformance.org/case-study-briefs/mission-creek)

From a landscape architect’s perspective, bioretention basins are attractive because they are:

-

Flexible in form – they can be linear, curved, isolated cells or continuous beds.

-

Scalable – from small residential rain gardens to large campus courtyards.

-

Visually rich – planting design can communicate seasonal change, habitat and identity.

The trade-offs are largely operational. Without committed maintenance, inlets clog, sediment builds up, and planting can drift into something that looks “weedy” to many users (Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, 2013). Sizing is critical: if the contributing catchment is large and available land is small, it is easy to promise more performance than the basin can realistically deliver (IWA, 2022).

Yet, where municipalities and institutions set clear water-quality targets or pursue sustainability certifications such as LEED or SITES, bioretention frequently becomes the default choice: it is technically robust, relatively familiar to regulators, and visually compatible with almost any design language.

Bioswales: Stormwater in Motion Along the Street Edge

If bioretention basins are the “nodes” in a network, bioswales are the “lines”. A bioswale is a vegetated, gently sloped channel that conveys stormwater while promoting infiltration and pollutant removal along its length. Compared with a basin, a bioswale expresses water as movement rather than as a static pool (Urban Green–Blue Grids, n.d.; EPA, n.d.).

Bioswales have become emblematic of green street design. Portland, Oregon, for example, has turned entire corridors into living laboratories for stormwater. The SW 12th Avenue Green Street, designed by Nevue Ngan Associates with landscape architect Kevin Robert Perry, replaces a conventional curb and gutter with a sequence of recessed planting areas. Street runoff enters through curb cuts, passes through soil and vegetation, and exits cleaner into the piped network. For pedestrians, the experience is of walking along a leafy, textured edge rather than beside a sheer kerb (City of Portland BES, 2010; Perry, 2010).

Source: (courses.washington.edu/gehlstud/gehl-studio/wp-content/themes/gehl-studio/downloads/Autumn2008/Portland_Green_Streets.pdf)

On the other side of the continent, the Oros Green Street in Los Angeles, delivered by non-profit North East Trees with the city, applies a similar logic in a residential neighborhood: bioswales and infiltration areas manage urban runoff to protect the Los Angeles River, while also calming traffic and greening the street (City of Los Angeles, 2011).

Source (urbanecologycmu.wordpress.com/2015/10/22/oros-green-street-project_stormwater-management/)

For designers, bioswales are often the only realistic way to introduce sponge functions into streets where right-of-way is constrained and utilities compete for underground space. They create a linear buffer between vehicles and pedestrians, give structure to planting, and support continuous habitat corridors.

However, the simplicity of the section hides several challenges. Slopes that are too steep invite erosion and bypass; slopes that are too flat create ponding and maintenance issues. Driveways and crosswalks interrupt flow and need careful detailing. And, as with bioretention, these systems catch litter as well as water: governance arrangements must include regular cleaning and vegetation management (Im et al., 2019; Koucka, 2025).

Water Squares: Flood Infrastructure as Civic Stage

Where bioretention basins and bioswales hide their technical sophistication within apparently familiar planting, water squares do the opposite: they stage stormwater infrastructure as architecture.

Pioneered in Rotterdam by De Urbanisten, a water square is a public plaza that doubles as a temporary stormwater reservoir. Most of the time it functions as a hard, usable urban space. During heavy rain, depressed areas fill with water captured from surrounding roofs and streets, then slowly drain or infiltrate once the storm has passed (De Urbanisten, n.d.).

The most famous example, Water Square Benthemplein, is organised into three basins of differing depth, each with a distinct programme. The deepest bowl is used as a sports court and performance space when dry; shallower basins support seating, planting and informal play. During cloudbursts, water arrives dramatically through overhead gutters and small waterfalls, transforming the square into a temporary urban lake. The project emerged from Rotterdam’s broader “Waterplan 2” climate adaptation strategy and was financed largely through water management budgets (Peinhardt, 2021; Mariano, 2020).

Source: (urbanisten.nl/work/benthemplein)

What is striking here is the inversion of traditional practice. Rather than burying storage tanks below ground and simply repaving the surface, the design makes water storage the main organising principle of the public space. Landscape architects play the role of translator between hydraulic engineers, who size the basins and control structures, and local communities, who need a square that feels welcoming 365 days a year, not just photogenic for a few storms.

Other cities have adopted similar ideas. Copenhagen’s climate-adapted neighborhoods, for example, incorporate stepped “water plazas” that can flood during intense rainfall while functioning as everyday parks and sports courts the rest of the time (Mariano, 2020).

Water squares are not the right tool for every context. They require a relatively large, contiguous space in dense urban fabric, a tolerance for surfaces that occasionally become inaccessible, and governance frameworks that can manage safety and liability. But where those conditions exist, they turn a regulatory obligation – cloudburst storage – into a civic asset.

Sponge Parks: Cleaning the Industrial Past

Where water squares are primarily about flood volumes, sponge parks are often about pollution legacies.

The term “sponge park” is more conceptual than technical. It describes parks whose primary structure is stormwater capture, treatment and storage. The best-known example is the Gowanus Canal Sponge Park™ in Brooklyn, designed by DLANDstudio Architecture + Landscape Architecture under Susannah Drake.

Source: (architectmagazine.com/project-gallery/gowanus-canal-sponge-park-masterplan_o)

The Gowanus Canal is one of the most contaminated waterways in the United States. Combined sewer overflows and historic industrial discharges left sediments laced with pollutants. DLANDstudio’s masterplan envisions a network of linear parks and wetland cells along the canal and throughout its watershed. These “sponge” elements intercept and treat stormwater before it reaches the canal, using a combination of bioretention soils, wetland vegetation and controlled discharge structures (Drake, 2011; DLANDstudio, n.d.).

The built pilot segment demonstrates how this works: a narrow strip of public open space along the canal edge incorporates modular wetland units, a promenade and seating. For visitors, it is a small waterfront park. Hydrologically, it is a piece of distributed treatment infrastructure contributing to Superfund clean-up objectives.

Projects such as Manchester Stormwater Park in Washington State (Parametrix) and Mission Creek Stormwater Park (CMG) share the same DNA. They transform underused or degraded land into public parks shaped primarily by hydrological functions: spiralling rain gardens, terraces and channels that filter polluted runoff before discharge into ecologically sensitive waters.

For landscape architects, sponge parks present both a technical and an ethical project. They require grappling with contaminated soils and sediments, complex phasing tied to clean-up schedules, and the expectations of communities who may have suffered environmental injustice for decades. They also offer a powerful narrative: the park is not just a new amenity, but part of a long process of repair.

How Landscape Architects Decide: A Practice Framework

In practice, these four typologies are rarely deployed in isolation. A single precinct plan might include bioswales along streets, bioretention basins in courtyards, a sponge-like waterfront park and, at its centre, a floodable plaza. What matters is the underlying logic.

When landscape architects sit down with a brief, four questions tend to shape the choice of tools.

1. What hydrological problem are we really solving?

Is the primary challenge frequent, localised pluvial flooding, or chronic water-quality impairment, or both? Water squares are powerful where short-duration, high-intensity storms threaten dense centres; sponge parks often respond to long-standing pollution problems; bioretention and bioswales can be tuned to a wide range of volume and quality targets if applied at scale across a catchment (Gross, 2009; Im et al., 2019).

2. What does the urban form allow?

Linear rights-of-way lend themselves to bioswales and bioretention planters. Campus malls, plazas and parking courts favour bioretention basins and small “water square” gestures. Waterfront brownfields and canal edges naturally point toward sponge park solutions. Firms such as Atelier Dreiseitl (now Ramboll Studio Dreiseitl) have shown in projects like Kronsberg in Hannover how swales and basins can be woven into the basic structure of new neighbourhoods from the outset (Urban Green–Blue Grids, n.d.).

3. What programmes and experiences do we want to enable?

Universities often value visible, didactic systems: students can literally see where stormwater goes in projects like the University of Georgia’s Science Learning Center or ASU’s Orange Mall, both documented in the Landscape Architecture Foundation’s Landscape Performance Series. City centres may prioritise spaces that can host events, sports and everyday life, making water squares attractive. Residential streets benefit from bioswales and sponge-like frontages that buffer pedestrians from traffic.

4. Who will own and maintain the system?

The most brilliant hydrological concept fails if no one budgets to maintain it. Simple bioswales may suit a municipality with limited resources. Highly designed water squares or sponge parks require clear agreements between parks departments, utilities and sometimes separate water boards. In Rotterdam, De Urbanisten’s work was only possible because the water authority agreed that its budget could be spent on public space that also met hydraulic performance criteria (Peinhardt, 2021).

Framed in this way, bioretention basins, bioswales, water squares and sponge parks are less a menu of isolated objects and more a portfolio of strategies. Landscape architects configure that portfolio to local conditions, budgets and governance arrangements.

Conclusion: Toward an Aesthetic of Performance

What unites all of these typologies is the insistence that performance and place are not trade-offs.

Bioretention basins can be more than engineered pits; they can be the backbone of a campus or neighbourhood landscape. Bioswales can be more than “green ditches”; they can redefine the image of a street. Water squares transform flood storage from an invisible cost into a public asset and symbol of resilience. Sponge parks make environmental repair legible along some of the most damaged urban waterfronts.

For landscape architects, this is both an opportunity and a responsibility. The opportunity lies in claiming a central role in infrastructure delivery, working shoulder to shoulder with engineers and water managers. The responsibility lies in ensuring that these landscapes are not short-lived pilot projects but durable systems whose beauty, ecological value and hydraulic performance endure beyond the first funding cycle.

As climate pressures grow, cities will increasingly be judged by how intelligently they handle water – not just behind the scenes, but in the spaces where people live their daily lives. The move from concrete to sponge is already under way. The next chapter will be written, quite literally, in the sections and planting plans of landscape architects.

Featured Posts

Blog Topics

Urban environment & Public spaces

Stay updated with the latest articles and insights from The Landscape Lab. Here, you will find valuable information and engaging content.

Waterfront & Coastal Resilience

Stay updated with the latest articles and insights from The Landscape Lab. Here, you will find valuable information and engaging content.

Captivating Photography

Stay updated with the latest articles and insights from The Landscape Lab. Here, you will find valuable information and engaging content.

Why Read The Landscape Lab Blog?

The way we design and interact with landscapes is more important than ever. As cities expand, coastlines shift, and climate change reshapes our world, the choices we make about land, water, and urban spaces have lasting impacts. The Landscape Lab Blog is here to spark fresh conversations, challenge conventional thinking, and inspire new approaches to sustainable and resilient design.

If you’re a landscape architect, urban planner, environmentalist, or simply someone who cares about how our surroundings shape our lives, this blog offers insights that matter. We explore the intersections between nature and the built environment, diving into real-world examples of cities adapting to rising sea levels, innovative waterfront designs, and the revival of native ecosystems. We look at how landscapes can work with nature rather than against it, ensuring long-term sustainability and biodiversity.

By reading The Landscape Lab, you'll gain a deeper understanding of the evolving field of landscape design—from rewilding initiatives to regenerative urban planning. Whether it’s uncovering the forgotten history of resilient landscapes, analyzing groundbreaking projects, or discussing the future of green infrastructure, this blog provides a space for learning, inspiration, and meaningful dialogue.

Location:

The Landscape Lab

123 Greenway Drive

Garden City

NY 12345

United Kingdom

Contact Number:

Get in Touch:

contact@thelandscapelab.co.uk

© 2025 thelandscapelab.co.uk - Your go-to blog for landscaping insights